Expert opinion on the management of esophageal achalasia from the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) Global Outreach Committee

Introduction

Background

Achalasia is often considered a rare disease, but its incidence varies globally. One US study reported 10–26 cases per 100,000 people annually (1), compared to 4.7 per 100,000 for esophageal cancer in the same country (2). Achalasia may be as common as esophageal cancer, yet it is frequently misdiagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and other benign and malignant diseases of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ), leading to treatment delays. Nearly half of achalasia patients in one series were on antacid medication, wrongly diagnosed with GERD (3). Misdiagnosis among surgeons during laparoscopic antireflux surgery may reach up to 4% of cases (4).

Rationale and knowledge gap

To address these issues, the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) Global Outreach Committee organized a panel of experts at their 65th annual meeting to discuss achalasia management.

Objective

This review compiles their opinions and recommendations.

Methods

This expert opinion paper summarizes the current evidence-based data and personal experience of a panel of experts for achalasia.

The experts were lecturers invited by the SSAT Global Outreach Committee during the 65th annual meeting in Washington, DC, USA in May 2024. Topics were selected by the members of the Committee to include diagnoses and treatment. All presenters were requested to send their lectures that were compiled together and revised by the whole group.

Diagnoses

Symptoms

Symptoms can occur due to the functional obstruction of the esophagus and EGJ (dysphagia, regurgitation), its consequences (weight loss, halitosis, heartburn due to food fermentation and acid production in the esophagus), spastic uncoordinated contractions (chest pain) or aspiration (cough). Dysphagia, regurgitation, and weight loss are, however, the common triad of symptoms in patients with achalasia. It is noteworthy that symptoms are common to other esophageal disorders including GERD. The Eckardt score is certainly the most used grading system (5) (Table 1). Eckardt scores range from 0 to 12, with a score of 3 or less considered ‘normal’ or minimally symptomatic.

Table 1

| Score | Dysphagia | Regurgitation | Chest pain | Weight loss (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None | None | None |

| 1 | Occasional | Occasional | Occasional | <5 |

| 2 | Daily | Daily | Daily | 5–10 |

| 3 | Each meal | Each meal | Each meal | >10 |

Each item is graded on a score of 0 to 3, with a maximum score of 12. Symptoms are frequently considered relevant with a final score >3. Based on reference (6).

Upper digestive endoscopy

Upper digestive endoscopy is essential when achalasia is suspected but does not diagnose the disease. It appears normal in half of the cases, while the other half may show indirect signs like food residue (despite adequate fasting), leukoplakia, or puckering at the gastroesophageal junction. The endoscopist may notice the esophageal dilatation in cases with marked dilatation. Resistance to passing of the scope may be noticed, even though the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) opens even in normal individuals only in response to swallowing what does not occur during sedation. This may raise the suspicion of pseudoachalasia due to a hidden malignancy at the EGJ.

Endoscopy mainly aims to rule out other conditions, especially esophageal cancer, since achalasia increases the risk of squamous cell cancers (7). The risk is, apparently, not decreased by therapy. Thus, endoscopic surveillance is advisable. The ideal interval between tests is, however, unclear. We believe that an endoscopy at least every 4 or 5 years is recommended.

Posttreatment, endoscopy may be necessary to evaluate dysphagia recurrence but especially to evaluate GERD that has a variable incidence after therapy as it will be discussed along the paper.

Barium esophagogram

A barium esophagogram is a straightforward test for diagnosing and grading the disease. A massively dilated esophagus with tapering of the distal portion (bird’s beak sign) usually does not have significant differential diagnoses. Minor dilatation without the bird’s beak sign may be observed in connective tissue disorders with aperistalsis (8) or in advanced GERD with aperistalsis. Less pronounced esophageal dilatation with tapering can result from tumoral obstruction and pseudoachalasia (4). Even when diagnosis is achieved through other methods, an esophagogram can serve as a baseline for comparison following therapy in cases of treatment failure. Additionally, aside from aiding in diagnosis, the extent of esophageal dilatation may help grade the disease and identify end-stage conditions.

Timed barium swallow measures the contrast column after a set volume and time to evaluate esophageal emptying. It can help in unclear cases and is often used post-treatment to check if there is persistent outflow obstruction at the EGJ in case of dysphagia recurrence (9).

Esophageal manometry

Achalasia was defined during the conventional manometry era as a failure of complete relaxation of the LES and aperistalsis as identified as 100% of simultaneous or absent waves. High-resolution manometry did not change this definition even though LES relaxation is measured by a more complex and supposedly better parameter—integrated relaxation pressure (IRP)—and aperistalsis is measured by the presence of failed waves (10).

Some Latin American authors believe in what they call an “undetermined” stage of achalasia. This stage is assumed to occur in patients with Chagas’ disease but depicting manometric findings other than the classical definition (unrelaxing LES and aperistalsis) assuming that this is an initial stage presupposing that they would eventually evolve to aperistalsis (11). In our experience, we have never seen such cases (12). Patients with Chagas’ disease may never develop esophagopathy and the manometric findings that do not characterize achalasia may be secondary to GERD (13).

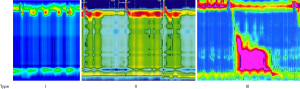

A widely adopted classification is the Chicago Classification that defines three types of achalasia based on esophageal pressurization during swallows (Figure 1) (14). This classification gained acceptance due to the fact that it is linked to prognosis (15) and may guide therapy (16). Several variants have been identified, but it is unclear if they need the same or different treatments. Moreover, lack of dedicated studies leads to a very low level of recommendation (17). The Chicago Classification 4.0 presented 32 recommendations: 18 (56%) were strong recommendations while the other 14 (44%) were conditional recommendations or accepted clinical observations. The level of supportive evidence, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) process, was moderate in 2 (9%) instances, low in 11 (52%), and very low in 8 (38%).

The group from the University of Rochester first described variants that challenged the concept of “all or nothing at all” to aperistalsis as a prerequisite for the disease (18). The group advocated that the disease may start in the LES and aperistalsis may be a secondary, metachronous finding. They described the following variants: subtype 1, abnormal LES relaxation with normal/hypertensive peristalsis; subtype 2, abnormal/borderline LES relaxation with mixed peristalsis or simultaneous waves; and subtype 3, abnormal/borderline LES relaxation and aperistalsis with occasional short segment peristalsis. This classification, however, never gained popularity.

Chicago Classification (19) described variants that denote an inconclusive diagnosis and demand further investigation with other tests. They are: (I) absent contractility with no appreciable peristalsis in the setting of IRP values at the upper limit of normal in both positions, with or without panesophageal pressurization in 20% or more swallows; (II) appreciable peristalsis with changing position in the setting of a type I or II achalasia pattern in the primary position; and (III) abnormal IRP with evidence of spasm and evidence of peristalsis. Again, the evidence provided is low (17). Furthermore, normal IRP is frequently observed, occurring in over half of the cases in our series (20). This is compounded by the fact that surgeons might receive patients after an endoscopic treatment that disrupts the LES, thereby compromising its manometric analysis.

Provocative tests may be added to the test. This complementation is based on very low levels of evidence (17), with discrepant results (21), makes the test longer, losing one of the advantages of high-resolution manometry and leads to the battle between the findings of conflicting results—before and after provocation (22).

This increase in complexity from the simple aperistalsis to numerous variants leads to an interobserver agreement for the manometric diagnosis of achalasia ranging between 75% and 84% even including experienced interpreters (23-26). It is too soon to determine if artificial intelligence will improve these numbers (27).

Functional lumen imaging probe

Endolumenal functional lumen imaging probe (EndoFLIP) measures EGJ compliance. It is described by the Chicago Classification as a supportive test in cases of inconclusive diagnosis (19). It may identify abnormal EGJ distensibility in patients with typical achalasia symptoms but without classic manometric features of achalasia (28).

pH monitoring

GERD is paradoxical in treatment naïve cases since the lack of LES relaxation forbids flux and reflux. Pseudoreflux, however, may occur due to intraluminal food fermentation and intrinsic acid production (7).

Other tests

Other tests to assess extraesophageal disease may be used if pseudoachalasia is suspected, such as endoscopic ultrasound and tomography (4).

Treatment

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)

POEM is the newest of the most common procedures on the continuum of achalasia treatment. Like other surgical interventions, it involves cutting the LES. Surgical division of the LES is the gold standard treatment of achalasia since Heller’s open myotomy was first performed in 1913. This was transitioned to a thoracoscopic myotomy in 1992 and a laparoscopic myotomy in 1993. In 2010, Inoue presented his first series of POEM for achalasia (29).

POEM is indicated for disorders of outflow including all subtypes of achalasia. It can also be used for sole treatment in the setting of epiphrenic diverticulum (30). It has also seen success in disorders of esophageal peristalsis including distal esophageal spasm (DES) and hypercontractile esophagus (31). It is important to exercise caution in the use of POEM in these instances, as some cases of DES and hypercontractile esophagus are actually secondary effects of GERD (32). There are some cases where POEM has a distinct advantage over traditional approaches to esophageal myotomy. In cases where patients have had a prior myotomy, doing a peroral myotomy on the opposite side of the esophagus can be a relatively scar-free plane with acceptable success and lower morbidity than an attempt at redo laparoscopic or thoracoscopic myotomy (33).

In type 3 achalasia, some argue that there is a superior rate of symptom improvement for POEM as compared to traditional myotomy (34). A meta-analysis concludes for this premise (16); however, the evidence underpinning this is quite weak—cohort studies with short-term follow-up are often compared with longer-term outcomes following myotomy and an outlier in the meta-analysis did not use an extended Heller myotomy affecting final result. Finally, in cases where patients have had prior foregut surgery, an endoscopic approach to myotomy can be more straightforward.

In comparison to surgical myotomy, POEM has comparable success rates (35). Thus, most gastroenterology and gastrointestinal surgical societies advocate that POEM is a reasonable option for patients in a setting with appropriate local expertise and if patient preference dictates. Overall, there has been persistent use of surgical myotomy for achalasia over time, but there has been a notable increase in POEM usage.

In comparison to nonsurgical treatments like pneumatic dilation (PD), randomized controlled trials have shown higher success rates with POEM over PD (92% as compared to 54%) with a lower rate of adverse events (0% vs. 7%). This is likely due to the more controlled nature of the circular muscle division in POEM. The GERD rate after POEM, and consequent need to long-term medication usage, is somewhat higher than after PD, unsurprising as it is more effective in relaxing the esophagogastric barrier for symptom relief in achalasia (36).

In comparison to Heller myotomy, POEM is equally successful in randomized controlled trials. In a study by Werner et al. clinical success rate for POEM and Heller plus fundoplication were comparable (83% vs. 81.7%) with a similar rate of adverse events (2.7% for POEM and 7.3% for Heller) (35). Again, reflux rate was somewhat higher after POEM at 44% compared to Heller’s 29%, but this was not statistically significant. This randomized controlled data cemented POEM as a mainstay in the armamentarium of esophageal surgeons. More recent studies have also concluded that GERD rate over time decreases with POEM (37).

Inadequate myotomy has long been one potential risk of surgery for achalasia. Often, this is inadequate extension of myotomy onto the stomach. In the case of POEM, adjunct intraoperative testing like use of a second scope within the lumen to verify tunnel length can decrease the likelihood of incomplete tunneling and incomplete myotomy (38). Additionally, use of EndoFLIP during POEM can help target an esophageal diameter and distensibility index (DI) that is more likely to lead to clinical success (39). Current EndoFLIP parameters during POEM are guided based off of cohort data as well as studies evaluating these parameters in normal subjects (40). Early EndoFLIP data during POEM was collected using EndoFLIP 1.0. This found that DI of 4.5–8.5 was optimal (39). However, more recent studies using the updated EndoFLIP 2.0 system have shown that a DI less than 3.1 correlates with treatment failure (41). The same research group found that a DI of over 2.7 and/or a diameter over 11 mm is more likely to develop esophagitis (42). The conclusion for this early EndoFLIP data in POEM is that there is an overall lack of standardization of parameters to determine adequacy of myotomy with EndoFLIP. However, in general there is evidence that the use of EndoFLIP is associated with better outcomes. Over time, the use of EndoFLIP may allow the length of myotomy to become shorter with comparable symptom improvement. There is evidence that a shorter endoscopic myotomy can effectively treat achalasia with equivalent rates of success, but with a lower risk of GERD and esophagitis (43,44). This provides an exciting opportunity to continue to optimize POEM for achalasia.

One of the challenges of POEM is the steep learning curve some experience. In general, endoscopists who have robust interventional practice are able to adopt POEM with a learning curve that varies between 13 and 20 cases (45-47). Longitudinal training with an expert operator can also lead to successful adoption, and fellowships in minimally invasive surgery as well as third space endoscopy have the potential to train surgeons and gastroenterologists to perform POEM. Current formal training pathways include a general surgery residency plus a minimally invasive fellowship with an endoscopic focus, a medicine residency plus a GI fellowship followed by an advanced endoscopy fellowship, and a thoracic surgery residency plus advanced endoscopy fellowship. Informal training pathways outside of fellowship are numerous and include a practice of interventional endoscopy plus ideally ESD, plus didactic training and hands-on skill sessions through surgical and gastroenterology societies, plus proctored early cases. These training pathways are in evolution as the technical worlds of GI surgery and interventional endoscopy continue to develop. What is likely to continue to be true is that POEM is a mainstay for achalasia treatment, is equivalently effective when compared to Heller myotomy and is largely superior to PD. Reflux after POEM is a continuous debate and lacks good study including pH monitoring. Finally, tailoring POEM with EndoFLIP is likely to improve outcomes.

Laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM)

Surgical treatment for esophageal achalasia was introduced by Heller in 1913, consisting of an anterior and posterior myotomy across the LES (48), but the current technique was modified in 1923 by Zaaijer to simply an anterior myotomy (49). LHM was first described by Shimi et al. in 1991 (50). With the minimally invasive surgery revolution, the Padova group was the first to propose the laparoscopic myotomy with the addition of a Dor fundoplication [LHM + Dor (LHD)] (51). In a few years, LHD seems to have completely changed the achalasia management algorithm and it has rapidly become the procedure of choice for treating this disease. So far, a 6–7 cm anterior myotomy is performed, extending it 2–3 cm onto the proximal stomach. Early middle success rates with LHD have been high, around 90% (52,53) and the first 20 years follow-up study on a large cohort showed that >80% of patients were still symptom-free (54).

Looking at the available randomized trials and knowing that the definition of failure and when to recommend re-treatment remains ill-defined (55). One can clearly see that the outcome of LHD is similar than POEM and PD but with a lower incidence of intraoperative and long-term complications (35,56).

According to recent studies examining large cohorts of achalasia patients, the presence or absence of a sigmoid esophagus and the pre-operative manometric patterns represent the strongest predictors of outcome in terms of dysphagia and food-regurgitation relief (35,54-56). These data confirm the importance of a detailed pre-treatment work-up to define the patient’s radiological grade (57,58) and manometric subtype (59-61).

A recent study has demonstrated that the LHD myotomy with the “pull-down” technique is an effective treatment in more than 90% of patients with end-stage diseases and it should be the first surgical option offered to this difficult group of patients before considering esophagectomy (62).

Patients with manometric types I and II have better clinical outcomes after LHD than those with type III (55,59,60). Moreover, manometric studies showed that the LES is longer in type III achalasia, and that extending the myotomy both downwards and upwards could improve the outcome in this cohort of patients (63,64).

It is also not clear if age should therefore be considered a factor in the choice of treatment for achalasia. Curiously, most specialized centers do not tailor treatment based on advanced age (65). While two recent studies showed that LHD can be used as the first (and often only) therapeutic approach to achalasia in elderly patients with an acceptable surgical risk (65,66), endoscopic dilatation is also a possibility (65), but botulinum toxin injection offers unacceptable results even though it looks attractive in the elderly.

Moving to the point of view of children, recently the Padova group published the 25-year experience of LHD in pediatric patients and they concluded LHD is a safe and long-term effective treatment even in the pediatric age, with a success rate comparable to that usually obtained in the adult population (67).

LHD-related morbidity is very low. The main complications associated are mucosal perforations, which occur in 2–7% of patients (52,54). Most of them are detected during the procedure, however, and repaired intraoperatively, with no further clinical consequences or influence on the outcome (68). The procedure carries a really small mortality risk and is not correlated with the surgical procedure, so a careful patient selection needs to be done during the pre-treatment assessment.

The main long-term complication reported after LHD is GERD. In a recent report on a large series of 1,001 patients treated with LHD and assessed with an objective evaluation after surgery (24-h pH monitoring) only 9.1% of patients showed a pathological distal esophageal acid exposure (54). Comparing this complication between the other available treatments, in a recent Italian propensity score match trial, the incidence of GERD was statistically lower after LHD (17%) than after POEM (38.4%) (69). While the European trial showed no difference in distal esophageal acid exposure at 10 years follow-up between LHD and pneumatic dilatation (56).

In conclusion, LHD can durably relieve achalasia symptoms in more than 80% of patients at 20 years after treatment, comparable or superior to other treatment options (Table 2). Complications of surgery are rare, and postoperative reflux occurs in less than 10% of patients. The pre-operative manometric pattern and the presence of a sigmoid esophagus need to be assessed to appropriately modify the LHD: a longer myotomy (in pattern III) or the pull-down technique (in end-stage disease).

Table 2

| Authors | Year | Patient, n | Follow-up (months) | Treatments (A vs. B) | Outcome A (%) | Outcome B (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novais (70) | 2010 | 94 | 3 | PD vs. LHD | 73.8 | 88.3 | 0.08 |

| Persson (71) | 2015 | 39 | 78 | PD vs. LHT | 61 | 88 | 0.025 |

| Werner (35) | 2019 | 221 | 24 | POEM vs. LHD | 83 | 81.7 | n.s. |

| Sediqi (72) | 2021 | 43 | 120 | PD vs. LHT | 64 | 92 | 0.016 |

| Kuipers (73) | 2022 | 125 | 60 | PD vs. POEM | 40 | 81 | <0.01 |

| European trial (56) | 2024 | 76 | 120 | PD vs. LHD | 74 | 74 | n.s. |

LHD, laparoscopic Heller myotomy + Dor; LHT, laparoscopic Heller myotomy + Toupet; n.s., not significant; PD, pneumatic dilatation; POEM, peroral endoscopic myotomy.

Diagnosis and treatment of end-stage achalasia

The definition of end-stage achalasia is still a matter of debate. Most of the authors rely on the assessment of radiographic features. In 2018, the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus (ISDE) published a consensus guideline on achalasia, and specifically recommended barium esophagogram as the defining study in characterizing end-stage achalasia (57). The diagnostic radiographic feature is a massive dilation and tortuosity, which is termed sigmoid esophagus (Figure 2) (74). Manometry may be difficult to perform in the setting of end-stage achalasia due to dilation and tortuosity of the esophagus and retained debris that may lead to catheter looping or kinking without crossing the LES (57,75). Thus, a megaesophagus with sigmoid shape and distal esophageal sump would widely be considered representative of the end-stage achalasia.

A descriptive summary of current treatment and the disadvantage of each approach is presented in Table 3 (76).

Table 3

| Intervention | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| PD | Risk of perforation, sepsis, and bleeding |

| Botulinum toxin | Temporary effects (3–6 months): fibrosis |

| POEM | Higher risk of GERD; technically challenging in a sigmoid esophagus |

| Minimally invasive Heller myotomy | Risk of complications; improperly constructed fundoplication, fibrosis |

| Stapled cardioplasty | Intractable GERD; persistent regurgitation |

| Esophagectomy | Significant morbidity and mortality; high-volume centers; acceptable QoL |

| POPE | Risk of intraluminal injury; novel approach without long-term follow-up |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PD, pneumatic dilation; POEM, peroral endoscopic myotomy; POPE, peroral plication of the esophagus; QoL, quality of life.

The primary role of treatment in achalasia patients is to palliate symptoms, most commonly through disruption of the LES and allow gravity-dependent esophageal emptying. Moreover, the treatment for end-stage achalasia includes also reducing risk of aspiration and improvements of nutritional deficiencies related to the non-functional esophagus (76).

Endoscopic approaches such as PD or temporizing paralysis of the LES with botulinum toxin may be employed, but more definitive treatment with LES myotomy is preferred in candidates suitable for general anesthesia. The two most common approaches currently are minimally invasive Heller myotomy (LHM), which is typically performed transabdominally with concurrent partial fundoplication, and POEM. Megaesophagus and sigmoid esophagus are also atypical initial presentations of achalasia, and patients with end-stage disease have often failed one or more of these initial treatment methods (74,76,77).

There is no consensus on which surgical therapeutic approach should be used for the end-stage achalasia treatment. However, most experts agree that the most definitive treatment for achalasia is esophagectomy, and esophageal resection should be considered in patients with end-stage disease or progression that has failed a less aggressive approach, including LHM or POEM (74,76,78). Much of the literature is retrospective, relying on expert opinion, case series, and individual discussions with patients, based on treatment successes in high-volume esophageal centers.

Heller myotomy

LHM is suitable for treating achalasia, even with sigmoid or megaesophagus. The minimally invasive transabdominal approach focuses on the distal esophagus, LES, and cardia while avoiding most of the redundant intrathoracic esophagus (76,79,80).

A pull-down technique was introduced for certain patients with sigmoid esophagus to align the esophageal axis. By encircling the gastro-esophageal junction with a string (easy flow/Penrose drain), approximately 10 cm of the lower mediastinal esophagus is isolated. Multiple stitches are placed on each side and then tied to secure the esophageal wall to the diaphragmatic pillars. Once the esophageal axis is verticalized, the LHD is performed as previously described (63,81).

Salvador et al. [2023] (81) studied 73 patients diagnosed with end-stage achalasia with a sigmoid esophagus treated with LHM. Of the 73, 23 had previous endoscopic treatment. They showed satisfactory results in 71.2%. Regarding the failures (21 patients), five patients refused additional treatment, while all the others underwent endoscopic PD as the first retreatment, with a success of 56% (9/16). No dilation-related complications were recorded. Further treatments for persistent failures included: a redo myotomy in four patients, a Botox injection in one, POEM in one, and esophagectomy in one.

A recent systematic review also showed good outcomes for LHM in end-stage achalasia (82).

POEM

POEM is a widely accepted initial approach to achalasia; however, there is some discussion involving its efficacy in the setting of end-stage achalasia (64–73% clinical success rate) (83,84). The loss of the organ’s axis and dilation significantly increase the complexity of the technique and the likelihood of complications.

A major concern following myotomy is the development of reflux disease. In particular, the rates of reflux after POEM have been reported to be nearly double those after LHD at 44% (35).

Esophagectomy

Esophagectomy for benign disease is a topic of discussion over the years. However, esophageal resection is considered definitive management for a non-functional esophagus. The restoration of alimentary continuity using gastric or colonic interposition aims to improve emptying and subsequently reduce the risk of weight loss or aspiration (78,85). The goal of esophagectomy for end-stage achalasia is to remove esophageal obstruction and the inert reservoir creating a direct path for food and liquid to enter the stomach.

When performing an esophagectomy, there is significant variability in the approach (minimally invasive vs. open, transabdominal, transthoracic, or a hybrid approach) as well as in the choice of interposition conduit to restore alimentary continuity. One common option for interposition is the use of the stomach as a conduit, relying on the blood supply of the gastroepiploic artery to perfuse a surgically narrowed stomach that is positioned through the mediastinum or in a substernal position and anastomosed to the proximal esophagus. This choice of conduit requires a single anastomosis between the stomach and esophagus, and the intra-abdominal position of the stomach allows for relatively straightforward transposition into the thoracic cavity (12,13,76-78). While colon interposition is an option, achalasia is non-malignant and typically does not affect life expectancy. Over time, interposed colons may dilate and cause food and liquid stasis, replicating the issues of end-stage achalasia.

This surgical procedure presents several challenges, including: sigmoid deviation of the esophagus into the right chest; transmural inflammation causing adhesions to the pleura, trachea, and crura; neovascularization of hypertrophied esophageal muscle leading to bleeding and potential reoperation; and prior fundoplication resulting in abdominal adhesions that shorten the gastric conduit (4-6,85,86). In high-volume surgical centers, the overall rate of morbidity ranges 30–60%, with operative mortality of 3–5% (74,77).

Esophagectomy and gastric transposition are safe procedures with acceptable morbidity, mortality, and reasonable postoperative clinical results in benign diseases, representing the definitive and last option in the management of end-stage achalasia. However, this type of reconstruction after esophageal resection causes modifications in anatomy and physiology on the upper gastrointestinal tract. Resection or disruption of natural antireflux mechanisms, esophageal-gastric direct anastomosis, pyloric drainage, impairment of gastric motility, recovery of acid secretion from gastric conduit, impaired motility of esophageal remnant all contribute to esophageal stump mucosal damage (13). Gastric and duodenal refluxate have been documented in 60–80% of esophageal resected patients. Long-term follow-up has revealed some late complications: (I) increasing incidence of esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in the esophageal stump; (II) diffuse gastritis of the transposed stomach; and (III) development of carcinoma in the esophageal stump (87,88).

The pathogenesis of these three late complications can be attributed to the following factors: (I) resection of the EGJ; (II) recovery of gastric acid secretion over time after surgery; and (III) development of Barrett’s epithelium following esophagectomy and gastric tube reconstruction (86,88).

da Rocha et al. (87) have studied 101 patients who underwent esophagectomy and cervical gastroplasty and were followed-up prospectively for a mean of 10.5±8.8 years. All patients underwent clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological evaluation every 2 years. Gastric acid secretion was also assessed. The incidence of esophagitis in the esophageal stump (45.9% at 1 year, 71.9% at 5 years, and 70.0% at 10 years follow-up); gastritis in the transposed stomach (20.4% at 1 year, 31.0% at 5 years, and 40.0% at 10 or more years follow-up), and the occurrence of ectopic columnar metaplasia and Barrett’s esophagus in the esophageal stump (none until 1 year, 10.9% between 1 and 5 years, 29.5% between 5 and 10 years, and 57.5% at 10 or more years follow-up), all rose over time. Gastric acid secretion returns to its preoperative values 4 years postoperatively. Esophageal stump cancer was detected in the setting of chronic esophagitis in five patients: three squamous cell carcinomas and two adenocarcinomas. Barrett’s esophagus is also a common finding (89).

Peroral plication of the esophagus (POPE)

POPE is a technique that uses an endoscopic suturing device to plicate the esophagus in a distal to proximal manner to eliminate the distal esophageal “sump” and facilitates emptying. This procedure is still experimental and should be performed by a skilled endoscopist in a high-volume center under clinical research scrutiny. POPE may offer some advantages for refractory sigmoid esophagus. It is important to note that full-thickness bites may be taken with the endoscopic suturing device, and injury to adjacent mediastinal structures can be fatal (90).

Current recommendations comprise myotomy with either LHD or POEM as initial surgical treatment of end-stage achalasia. A dilated sigmoid esophagus may denote significant technical challenges for POEM compared to a minimally invasive transabdominal surgical myotomy. Esophagectomy should be considered as a treatment option for end-stage achalasia, particularly in patients who have failed less aggressive treatment modalities (58,76).

Conclusions

This is essentially an opinion paper. The review was not intended to include new findings to direct future research but to be a practical clinical guide based on academic experts from high-volume centers. This may introduce bias in the selection of reviewed papers but, nonetheless, they underpin the concepts exposed.

Diagnosing achalasia requires suspicion and a thorough workup. Upper endoscopy is essential to rule out malignancy or premalignant conditions. Barium swallow helps confirm achalasia and provides a baseline for esophageal diameter. Esophageal manometry is the gold standard for diagnosis and aids in prognosis and therapy selection. The routine use of endoluminal functional lumen imaging probe remains uncertain.

Several treatment options are available for non-advanced achalasia, including pneumatic dilatation, POEM, and LHM. Botulinum toxin injection is a conduct of exception at present. These first-line treatments offer similar outcomes in terms of dysphagia relief but vary in postoperative reflux results. End-stage disease is likely best managed with LHD. A dilated sigmoid esophagus may present significant technical challenges for POEM. Esophagectomy should be considered as a viable treatment option for patients who have not responded to less aggressive treatments.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-25-14/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-25-14/coif). F.A.M.H. serves as the unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Esophagus from September 2024 to August 2026. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gaber CE, Eluri S, Cotton CC, et al. Epidemiologic and Economic Burden of Achalasia in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:342-352.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel N, Benipal B. Incidence of Esophageal Cancer in the United States from 2001-2015: A United States Cancer Statistics Analysis of 50 States. Cureus 2018;10:e3709. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, et al. Clinical, radiological, and manometric profile in 145 patients with untreated achalasia. World J Surg 2008;32:1974-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zanini LYK, Herbella FAM, Velanovich V, et al. Modern insights into the pathophysiology and treatment of pseudoachalasia. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2024;409:65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schlottmann F, Neto RML, Herbella FAM, et al. Esophageal Achalasia: Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Diagnostic Evaluation. Am Surg 2018;84:467-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology 1992;103:1732-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schlottmann F, Herbella F, Allaix ME, et al. Modern management of esophageal achalasia: From pathophysiology to treatment. Curr Probl Surg 2018;55:10-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chatzinikolaou SL, Quirk B, Murray C, et al. Radiological findings in gastrointestinal scleroderma. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2020;5:21-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanagapalli S, Plumb A, Lord RV, et al. How to effectively use and interpret the barium swallow: Current role in esophageal dysphagia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2023;35:e14605. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbella FAM, Malafaia O, Patti MG. New classification for esophageal motility disorders (Chicago classification version 4.0©) and chagas disease esophagopathy (achalasia). Arq Bras Cir Dig 2022;34:e1624. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbella FA, Aquino JL, Stefani-Nakano S, et al. Treatment of achalasia: lessons learned with Chagas' disease. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:461-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vicentine FP, Herbella FA, Allaix ME, et al. High-resolution manometry classifications for idiopathic achalasia in patients with Chagas' disease esophagopathy. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:221-4; discussion 224-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pantanali CA, Herbella FA, Henry MA, et al. Nissen fundoplication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with Chagas disease without achalasia. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2010;52:113-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Yadlapati R, Gonlachanvit S, et al. Chicago Classification update (version 4.0): Technical review on diagnostic criteria for achalasia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021;33:e14182. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, et al. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1526-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andolfi C, Fisichella PM. Meta-analysis of clinical outcome after treatment for achalasia based on manometric subtypes. Br J Surg 2019;106:332-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbella FAM, Patti MG, Filho RM, et al. How changes in treatment guidelines affect the standard of care: ethical opinions using the Chicago 4.0 classification for esophageal motility disorders as example. Foregut 2022;2:111-5. [Crossref]

- Galey KM, Wilshire CL, Niebisch S, et al. Atypical variants of classic achalasia are common and currently under-recognized: a study of prevalence and clinical features. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:155-61; discussion 162-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0 Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021;33:e14058. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vicentine FP, Herbella FA, Allaix ME, et al. Comparison of idiopathic achalasia and Chagas' disease esophagopathy at the light of high-resolution manometry. Dis Esophagus 2014;27:128-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Misselwitz B, Hollenstein M, Bütikofer S, et al. Prospective serial diagnostic study: the effects of position and provocative tests on the diagnosis of oesophageal motility disorders by high-resolution manometry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:706-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbella FAM, Patti MG. Double-checking esophageal function tests. Comment on: Carlson et al. evaluating esophageal motility beyond primary peristalsis: assessing esophagogastric junction opening mechanics and secondary peristalsis in patients with normal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022;34:e14293. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nayar DS, Khandwala F, Achkar E, et al. Esophageal manometry: assessment of interpreter consistency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hernandez JC, Ratuapli SK, Burdick GE, et al. Interrater and intrarater agreement of the chicago classification of achalasia subtypes using high-resolution esophageal manometry. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:207-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox MR, Pandolfino JE, Sweis R, et al. Inter-observer agreement for diagnostic classification of esophageal motility disorders defined in high-resolution manometry. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:711-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Kim SE, Cho YK, et al. Factors Determining the Inter-observer Variability and Diagnostic Accuracy of High-resolution Manometry for Esophageal Motility Disorders. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;24:58-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fass O, Rogers BD, Gyawali CP. Artificial Intelligence Tools for Improving Manometric Diagnosis of Esophageal Dysmotility. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2024;26:115-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Savarino E, di Pietro M, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Use of the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe in Clinical Esophagology. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1786-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy 2010;42:265-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wessels EM, Schuitenmaker JM, Bastiaansen BAJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal diverticula. Endosc Int Open 2023;11:E546-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khashab MA, Familiari P, Draganov PV, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy is effective and safe in non-achalasia esophageal motility disorders: an international multicenter study. Endosc Int Open 2018;6:E1031-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Philonenko S, Roman S, Zerbib F, et al. Jackhammer esophagus: Clinical presentation, manometric diagnosis, and therapeutic results-Results from a multicenter French cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2020;32:e13918. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang Z, Cui Y, Li Y, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for patients with achalasia with previous Heller myotomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2021;93:47-56.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumbhari V, Tieu AH, Onimaru M, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) vs laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) for the treatment of Type III achalasia in 75 patients: a multicenter comparative study. Endosc Int Open 2015;3:E195-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Werner YB, Hakanson B, Martinek J, et al. Endoscopic or Surgical Myotomy in Patients with Idiopathic Achalasia. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2219-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ponds FA, Fockens P, Lei A, et al. Effect of Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy vs Pneumatic Dilation on Symptom Severity and Treatment Outcomes Among Treatment-Naive Patients With Achalasia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;322:134-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kum AST, De Moura DTH, Proença IM, et al. Gastroesophageal Reflux Waning Over Time in Endoscopic Versus Surgical Myotomy for the Treatment of Achalasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2022;14:e31756. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grimes KL, Inoue H, Onimaru M, et al. Double-scope per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM): a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2016;30:1344-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teitelbaum EN, Soper NJ, Pandolfino JE, et al. Esophagogastric junction distensibility measurements during Heller myotomy and POEM for achalasia predict postoperative symptomatic outcomes. Surg Endosc 2015;29:522-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson DA, Prescott JE, Baumann AJ, et al. Validation of Clinically Relevant Thresholds of Esophagogastric Junction Obstruction Using FLIP Panometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:e1250-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su B, Callahan ZM, Novak S, et al. Using Impedance Planimetry (EndoFLIP) to Evaluate Myotomy and Predict Outcomes After Surgery for Achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2020;24:964-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attaar M, Wong HJ, Wu H, et al. Changes in impedance planimetry (EndoFLIP) measurements at follow-up after peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Surg Endosc 2022;36:9410-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gu L, Ouyang Z, Lv L, et al. Safety and efficacy of peroral endoscopic myotomy with standard myotomy versus short myotomy for treatment-naïve patients with type II achalasia: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2021;93:1304-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Familiari P, Borrelli de Andreis F, Landi R, et al. Long versus short peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: results of a non-inferiority randomised controlled trial. Gut 2023;72:1442-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Zein M, Kumbhari V, Ngamruengphong S, et al. Learning curve for peroral endoscopic myotomy. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E577-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reja M, Mishra A, Tyberg A, et al. Gastric Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy: A Specific Learning Curve. J Clin Gastroenterol 2022;56:339-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurian AA, Dunst CM, Sharata A, et al. Peroral endoscopic esophageal myotomy: defining the learning curve. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:719-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heller E. Extramukose kardioplastic beim chronischen Kardiospasmus mit Dilatation des Oesophagus. Mitt Grenzeb Med Chir 1913;27:141-9.

- Zaaijer JH. Cardiospasm in the aged. Ann Surg 1923;77:615-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimi S, Nathanson LK, Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy for achalasia. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1991;36:152-4. [PubMed]

- Ancona E, Peracchia A, Zaninotto G, et al. Heller laparoscopic cardiomyotomy with antireflux anterior fundoplication (Dor) in the treatment of esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc 1993;7:459-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campos GM, Vittinghoff E, Rabl C, et al. Endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2009;249:45-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsiaoussis J, Athanasakis E, Pechlivanides G, et al. Long-term functional results after laparoscopic surgery for esophageal achalasia. Am J Surg 2007;193:26-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costantini M, Salvador R, Capovilla G, et al. A Thousand and One Laparoscopic Heller Myotomies for Esophageal Achalasia: a 25-Year Experience at a Single Tertiary Center. J Gastrointest Surg 2019;23:23-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Savarino EV, Salvador R, Ghisa M, et al. Research gap in esophageal achalasia: a narrative review. Dis Esophagus 2024;37:doae024. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boeckxstaens G, Elsen S, Belmans A, et al. 10-year follow-up results of the European Achalasia Trial: a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing pneumatic dilation with laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Gut 2024;73:582-9. [PubMed]

- Zaninotto G, Bennett C, Boeckxstaens G, et al. The 2018 ISDE achalasia guidelines. Dis Esophagus 2018; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sweet MP, Nipomnick I, Gasper WJ, et al. The outcome of laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia is not influenced by the degree of esophageal dilatation. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:159-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henderson RD. Esophageal motor disorders. Surg Clin North Am 1987;67:455-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvador R, Costantini M, Zaninotto G, et al. The preoperative manometric pattern predicts the outcome of surgical treatment for esophageal achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1635-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rohof WO, Salvador R, Annese V, et al. Outcomes of treatment for achalasia depend on manometric subtype. Gastroenterology 2013;144:718-25; quiz e13-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nezi G, Forattini F, Provenzano L, et al. The esophageal pull-down technique improves the outcome of laparoscopic Heller-Dor myotomy in end-stage achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faccani E, Mattioli S, Lugaresi ML, et al. Improving the surgery for sigmoid achalasia: long-term results of a technical detail. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:827-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvador R, Provenzano L, Capovilla G, et al. Extending Myotomy Both Downward and Upward Improves the Final Outcome in Manometric Pattern III Achalasia Patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2020;30:97-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zotti OR, Herbella FAM, Armijo PR, et al. Achalasia Treatment in Patients over 80 Years of Age: A Multicenter Survey. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2020;30:358-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvador R, Costantini M, Cavallin F, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy can be used as primary therapy for esophageal achalasia regardless of age. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:106-11; discussion 112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provenzano L, Pulvirenti R, Duci M, et al. Laparoscopic Heller-Dor Is a Persistently Effective Treatment for Achalasia Even in Pediatric Patients: A 25-Year Experience at a Single Tertiary Center. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2023;33:493-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvador R, Spadotto L, Capovilla G, et al. Mucosal Perforation During Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy Has No Influence on Final Treatment Outcome. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:1923-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costantini A, Familiari P, Costantini M, et al. Poem Versus Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy in the Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia: A Case-Control Study from Two High Volume Centers Using the Propensity Score. J Gastrointest Surg 2020;24:505-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Novais PA, Lemme EM. 24-h pH monitoring patterns and clinical response after achalasia treatment with pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:1257-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Persson J, Johnsson E, Kostic S, et al. Treatment of achalasia with laparoscopic myotomy or pneumatic dilatation: long-term results of a prospective, randomized study. World J Surg 2015;39:713-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sediqi E, Tsoposidis A, Wallenius V, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy or pneumatic dilatation in achalasia: results of a prospective, randomized study with at least a decade of follow-up. Surg Endosc 2021;35:1618-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuipers T, Ponds FA, Fockens P, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy versus pneumatic dilation in treatment-naive patients with achalasia: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:1103-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banbury MK, Rice TW, Goldblum JR, et al. Esophagectomy with gastric reconstruction for achalasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;117:1077-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menezes MA, Andolfi C, Herbella FA, et al. High-resolution manometry findings in patients with achalasia and massive dilated megaesophagus. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeSouza M. Surgical Options for End-Stage Achalasia. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2023;25:267-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres-Landa S, Crafts TD, Jones AE, et al. Surgical Outcomes After Esophagectomy in Patients with Achalasia: a NSQIP Matched Analysis With Non-Achalasia Esophagectomy Patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2021;25:2455-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gockel I, Timm S, Sgourakis GG, et al. Achalasia--if surgical treatment fails: analysis of remedial surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:S46-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbella FA, Patti MG. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and fundoplication in patients with end-stage achalasia. World J Surg 2015;39:1631-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Csendes A, Orellana O, Figueroa M, et al. Long-term (17 years) subjective and objective evaluation of the durability of laparoscopic Heller esophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia of the esophagus (90% of follow-up): a real challenge to POEM. Surg Endosc 2022;36:282-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvador R, Nezi G, Forattini F, et al. Laparoscopic Heller-Dor is an effective long-term treatment for end-stage achalasia. Surg Endosc 2023;37:1742-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orlandini MF, Serafim MCA, Datrino LN, et al. Myotomy in sigmoid megaesophagus: is it applicable? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2021;34:doab053. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ueda C, Abe H, Tanaka S, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for advanced achalasia with megaesophagus. Esophagus 2021;18:922-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nabi Z, Ramchandani M, Basha J, et al. Outcomes of Per-oral Endoscopic Myotomy in Sigmoid and Advanced Sigmoid Achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2021;25:530-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duranceau A, Liberman M, Martin J, et al. End-stage achalasia. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:319-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinotti HW, Cecconello I, da Rocha JM, et al. Resection for achalasia of the esophagus. Hepatogastroenterology 1991;38:470-3. [PubMed]

- da Rocha JR, Ribeiro U Jr, Sallum RA, et al. Barrett's esophagus (BE) and carcinoma in the esophageal stump (ES) after esophagectomy with gastric pull-up in achalasia patients: a study based on 10 years follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:2903-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- da Rocha JR, Cecconello I, Ribeiro U Jr, et al. Preoperative gastric acid secretion and the risk to develop Barrett's esophagus after esophagectomy for chagasic achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1893-8; discussion 1898-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsiouris A, Hammoud Z, Velanovich V. Barrett's esophagus after resection of the gastroesophageal junction: effects of concomitant fundoplication. World J Surg 2011;35:1867-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hedberg HM, Attaar M, McCormack MS, et al. Per-Oral Plication of (Neo)Esophagus: Technical Feasibility and Early Outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg 2023;27:1531-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Herbella FAM, Shada AL, da Rocha JRM, Ribeiro U Jr, Velanovich V, Salvador R. Expert opinion on the management of esophageal achalasia from the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) Global Outreach Committee. Ann Esophagus 2025;8:13.