Potential missed opportunities for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of eosinophilic esophagitis: analysis of endoscopic food impaction management

Highlight box

Key findings

• Patients who did not receive a biopsy at the time of initial food impaction were more likely to present with repeat food impactions, were less likely to be given treatment recommendations, and had low rates of follow-up. Some of these patients were later diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) at subsequent food impaction encounters.

What is known and what is new?

• EoE is a common etiology behind food impaction.

• Gross findings suggestive of EoE may not be present or may not be recognized at the time of food impaction which could contribute to low biopsy rates.

• Delay in diagnosis may allow for worsening fibrosis and structural damage.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Given the high frequency of EoE in patients presenting with food impactions, standardizing biopsies would expedite the diagnostic process, lessen treatment delay, and possibly improve disease morbidity.

Introduction

In adults, esophageal and gastric foreign bodies are typically accidental with food bolus impaction being one of the most prevalent. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) both produce guidelines regarding management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract including food impaction (1,2). However, many of these recommendations are based on low-quality evidence.

Esophageal food impaction can be a common initial presenting symptom in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Patients presenting with food bolus impaction are often not biopsied during extraction. In a survey of three major gastroenterology societies in the US, only 34% of 428 respondents said they obtained esophageal biopsies at the time of food impaction. This study concluded that over 10,000 patients presenting with food impaction are at risk of being undiagnosed with EoE (3). Additionally, the gross appearance of the esophagus has been found to be a poor predictor of EoE and without biopsy, EoE may potentially be missed (4-7). Furthermore, follow-up has been found to be low; in two prior studies looking at food impaction and EoE, 54.5% and 32% were lost to follow-up, respectively (8,9). The infrequent rate at which esophageal biopsy is performed has important ramifications for delayed or missed diagnoses and any corresponding treatment that may otherwise prevent future complications. Even a delay in diagnosis by 6 years can increase stricture formation from 17.2% to 70.8% (10).

We hypothesize that many patients presenting with food impaction will have EoE and delay in diagnosis may lead to unnecessary morbidity. Our data could add to limited prior studies to increase awareness and advocate for biopsy on initial presentation. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://aoe.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/aoe-24-1/rc).

Methods

Study design

Data were collected at a tertiary medical center from one large referral institute by manually reviewing charts in the electronic medical record (EMR). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the institutional ethics board of Wake Forest University Health Sciences IRB00000212 and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

All patients from January 2017 through March 2020 who had undergone an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with the diagnosis code for foreign body removal were included. There were 136 patients where food was the primary object removed. Patients were further screened to make sure they met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were food bolus impaction at time of presentation, age 18 years and above, and receiving an EGD at the time of food impaction. Exclusion criteria were esophageal blockage not due to a food bolus, patients with prior established diagnosis of EoE, and patients with other etiologies which would explain food impaction including esophageal cancer, external compression of the esophagus, esophageal outflow obstruction, or achalasia. One hundred patients were ultimately included in the study.

Data collection

Multiple variables were collected from the EMR for each patient including: demographics, distance from the hospital, insurance status, if the patient had a primary care provider (PCP), history of gastrointestinal conditions, if a biopsy was taken at the time of food bolus removal, treatment recommendations, location of biopsy if performed, subsequent diagnosis of EoE on future biopsy, complications, other EGD findings, the attending overseeing the procedure and their subspecialty, if follow-up was scheduled and if they presented to follow-up, if the patient had a subsequent food bolus impaction, and type of removal device. Patients were considered to have a follow-up scheduled if follow-up was reported to be arranged in the EGD report, if the patient had a gastroenterology or surgery clinic visit within the next year, or if they had a subsequent gastrointestinal testing procedure scheduled for a separate hospital encounter within the next year. Patients were considered to have followed up if they presented to any of the above testing or appointments.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test while quantitative data were analyzed with the t-test or ANOVA. A P value <0.05 was considered significant in analysis.

Results

Between January 2017 and March 2020, 401 patients had an encounter for foreign body removal by EGD with 444 total objects removed. Food was removed in 136 patients, iatrogenic objects in 232 patients (mostly surgical staples and displaced stents), and nonfood ingestions in 33 patients. One hundred out of 136 patients presenting with food bolus met our inclusion and exclusion criteria for the possibility of undiagnosed EoE as an etiology for their food bolus.

Demographics and findings for these 100 patients are listed in Table 1. These patients were primarily male and Caucasian. Most had insurance coverage. Very few had a diagnosis of any atopic disease. Only 28% were biopsied at the time of food bolus presentation. Three percent of patients were diagnosed with EoE at a subsequent encounter. Treatment recommendations mostly invoked PPI use but also included steroids and diet modification. Approximately 7% of patients who were biopsied and 32% of patients who were not biopsied were given no treatment recommendations. While 84 of the 100 patients had a scheduled follow-up appointment, only about half completed follow-up. In this cohort, 10% returned to the hospital at a later date with a subsequent food bolus impaction. The great majority of patients in this cohort were seen by general gastroenterologists.

Table 1

| Demographics/findings | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |

| Male | 68 |

| Female | 32 |

| Average age (years) | 62 |

| Race (%) | |

| Caucasian | 93 |

| African American | 6 |

| Other | 1 |

| Self-pay/Medicaid (%) | 17 |

| PCP (%) | 83 |

| Average distance from the hospital [range] (miles) | 56 [0–2,749] |

| Atopic disease (%) | 9 |

| Gross EGD findings suggestive of EoE (%) | 24 |

| Total patients biopsied (%) | 28 |

| Location of biopsy (%) | |

| Proximal esophagus | 15 |

| Mid esophagus | 2 |

| Distal esophagus | 15 |

| Gastric | 7 |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Diagnosed with EoE on initial encounter (%) | 10 |

| Diagnosed with EoE at a later date (%) | 3 |

| Treatment recommendation given (%) | |

| No recommendation | 25 |

| PPI | 48 |

| Diet | 1 |

| Steroids | 1 |

| PPI and diet | 25 |

| Follow-up scheduled (%) | 84 |

| Patients who followed-up (%) | 49 |

| Subsequent food bolus (%) | 10 |

| Specialty of provider performing case (%) | |

| General practice GI | 80 |

| Advanced endoscopy: biliary | 5 |

| Hepatologist | 7 |

| Advanced endoscopy: ultrasound | 8 |

PCP, primary care provider; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; GI, gastrointestinal.

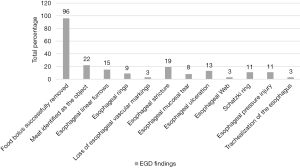

Findings on EGD are detailed in Figure 1. Typical EGD findings of EoE including linear furrows, rings/trachealization, and loss of vascular pattern were only seen in a minority of patients. In the 10% of patients who were diagnosed with EoE, all had gross findings on EGD suggestive of EoE.

Table 2 shows comprehensive follow-up data among these patients over 1 year. Eighty-four percent of all study patients had follow-up recommended or scheduled. Patients who did not have follow-up scheduled were also less likely to be given any treatment recommendations. Comparing patients who did and did not present for follow-up, younger age and not having a PCP were more likely to be seen in those without follow-up. Subsequent food bolus impaction (16.3% vs. 3.9%, P=0.04) was more likely in patients who presented to follow-up. (However, repeat food impaction would in itself classify as a follow-up given the generous follow-up criteria employed).

Table 2

| Parameters | Follow-up scheduled | No follow-up scheduled | P value† | Presented to follow-up | Lost to follow-up | P value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 84 | 16 | – | 49 | 51 | – |

| Average age (years) | 62.9 | 59.8 | 0.53 | 66.5 | 58.5 | 0.03 |

| Male (%) | 69 | 62.5 | 0.61 | 61.2 | 74.5 | 0.16 |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| Caucasian | 92.9 | 93.8 | 0.90 | 93.9 | 92.2 | 0.74 |

| African American | 6 | 6.3 | 0.96 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 0.97 |

| Other | 1.2 | 0 | 0.66 | 0 | 2 | 0.32 |

| Distance (miles) | 25.6 | 216 | 0.01 | 28.3 | 82.7 | 0.32 |

| Self-pay/Medicaid (%) | 15.5 | 25 | 0.36 | 10.2 | 23.5 | 0.08 |

| PCP (%) | 84.5 | 75 | 0.36 | 91.8 | 74.5 | 0.02 |

| Atopic disease (%) | 8.3 | 12.5 | 0.59 | 8.2 | 9.8 | 0.78 |

| Gross findings of EoE (%) | 25 | 18.8 | 0.60 | 18.4 | 29.4 | 0.20 |

| Biopsied (%) | 31 | 12.5 | 0.13 | 26.5 | 29.4 | 0.75 |

| Treatment recommended (%) | ||||||

| None given | 19 | 56.3 | 0.002 | 24.5 | 25.5 | 0.91 |

| PPI | 51.2 | 31.3 | 0.15 | 53.1 | 43.1 | 0.32 |

| Food | 1.2 | 0 | 0.66 | 2 | 0 | 0.31 |

| Steroids | 1.2 | 0 | 0.66 | 2 | 0 | 0.31 |

| PPI + food | 27.4 | 12.5 | 0.21 | 18.4 | 31.4 | 0.14 |

| Diagnosed with EoE (%) | 10.7 | 6.3 | 0.59 | 6.1 | 13.7 | 0.21 |

| Later diagnosed with EoE (%) | 3.6 | 0 | 0.44 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.08 |

| Subsequent food bolus (%) | 11.9 | 0 | 0.15 | 16.3 | 3.9 | 0.04 |

†, follow-up scheduled vs. no follow-up scheduled; ‡, presented to follow-up vs. lost to follow-up. PCP, primary care provider; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Table 3 shows data for patients who did and did not receive a biopsy at the index food impaction encounter. Patients who did not receive a biopsy were likely to be older, not be given treatment recommendations, and experience subsequent food impaction at a later date. Patients who were biopsied were more likely to have gross subjective findings suggestive of EoE.

Table 3

| Parameters | Biopsied | Not biopsied | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 28 | 72 | – |

| Average age (years) | 54 | 65.7 | 0.003 |

| Male (%) | 75 | 65.3 | 0.35 |

| Race (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 96.4 | 91.7 | 0.41 |

| African American | 0 | 8.3 | 0.12 |

| Other | 3.6 | 0 | 0.11 |

| Distance (miles) | 30.3 | 66.1 | 0.56 |

| Self-pay/Medicaid (%) | 21.4 | 15.3 | 0.47 |

| PCP (%) | 85.7 | 81.9 | 0.65 |

| Atopic disease (%) | 7.1 | 9.7 | 0.68 |

| Gross findings of EoE (%) | 46.2 | 15.3 | 0.001 |

| Treatment recommended (%) | |||

| None given | 7.1 | 31.9 | 0.01 |

| PPI | 50 | 47.2 | 0.80 |

| Food | 0 | 1.4 | 0.53 |

| Steroids | 0 | 1.4 | 0.53 |

| PPI + food | 42.9 | 18.1 | 0.01 |

| Diagnosed with EoE (%) | 35.7 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Later diagnosed with EoE (%) | 0 | 4.2 | 0.27 |

| Follow-up scheduled (%) | 92.9 | 80.6 | 0.13 |

| Followed-up (%) | 46.4 | 50 | 0.75 |

| Subsequent food bolus (%) | 0 | 13.9 | 0.04 |

PCP, primary care provider; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Data were also collected regarding food bolus removal. Slightly more than half of patients (51%) had their food bolus removed with a single device or method, 44% required multiple devices (net retriever, forceps, suction cap, snare, overtube with flushing, graspers, gentle push), and 5% of charts did not list the device or method employed. The most common single device/technique was the push technique with or without visualization distal to the bolus. Among patients in whom a single device was used (51% of the total), we further divided the data to compare the push technique vs. all forms of extraction. This technique was successful in 57% of patients compared to 43% for extraction devices (P=0.16). When comparing all patients where a known device was used (95% of the total), the push technique was used with or without an extraction device in 64% of cases, compared to extraction alone in 36% of cases (P<0.001). No major complications were reported for any patients during EGD.

Discussion

A total of 401 patients presented over a 3-year period with foreign body. Food impaction was the most common object removed in 136 of these patients. One hundred of these 136 patients met inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. As a tertiary medical center and a primary referral center for our region, our patients lived an average distance of 56 miles from the hospital. Of the patients with follow-up scheduled vs. no follow-up scheduled, there were no statistically significant demographic differences after excluding one patient who lived 2,749 miles from the hospital.

Only 28% of patients presenting with food impaction were biopsied in our study. We suspect poor awareness among gastroenterologists for the possibly of EoE as the etiology, hesitancy to biopsy an esophagus with existing trauma, and false sense of security regarding patient follow-up could all be contributing to this low biopsy rate.

Among patients who did and did not present for follow-up, older age and having a PCP were more likely among those who kept the follow-up appointment. This could suggest that presence of a PCP increases adherence to follow-up, or that these patients were generally more prone to seek healthcare and attend appointments. Insurance status was not significantly different among these patients with or without a PCP and likely not a cofounder for the difference in PCP status.

Looking at those who did not receive a biopsy at index EGD, only 50% presented to a follow-up appointment even when over 80% had a follow-up scheduled. Many EGD reports recommended returning for repeat biopsies, but clearly many patients are not adherent with this recommendation. This highlights the fact that these patients could benefit from biopsy at the time of presentation. Based on our results, we speculate a large portion of patients could potentially be undiagnosed and undertreated, which is consistent with a prior study (3). In our study, over 15% of the patients who were not biopsied had gross findings suggestive of EoE in their EGD reports. In addition, a higher percentage of patients not biopsied also received no treatment recommendations (31.9% vs. 7.1%, P=0.01). Thus, lack of treatment and counseling could underlie the return of a significant number of patients who had a subsequent food bolus encounter (13.9% vs. 0%, P=0.04). In addition, three out of 10 of these patients were later diagnosed with EoE. If these patients with possible EoE were biopsied and treated at the index encounter, fewer returns to the hospital may occur. Delay in the diagnosis of EoE is not unique to our study. A separate study found a median delay in diagnosis of 6 years, with prevalence of fibrotic features seen on endoscopy increasing from 46.5% to 87.5% and strictures increasing from 17.2% to 70.8% (10). These data suggest that standardization of guidelines could benefit such patients by yielding quicker diagnoses and appropriate care.

Given that we recommend biopsy during the initial encounter, we also examined any complications during EGD for those who received a biopsy along with the food removal technique. Although there were no direct complications reported following EGD, two patients eventually required surgical intervention for removal after EGD failed to remove food objects (it is unknown if they were later diagnosed with EoE). The push technique was the top choice for removing food followed by the Roth net. Although there was debate in the past surrounding the potential risk of perforation with the push technique, the ASGE and the ESGE both state that the push technique is acceptable in most situations (1,2). Our data agree with these guidelines that the push technique may be acceptable given that there were no reported complications in our cohort.

Current guidelines for determining when a biopsy should be taken are unclear or lacking. The ASGE recommends a biopsy of the mid and distal esophagus if EoE is suspected (2). This recommendation is not graded by evidence and, as noted, esophageal findings can be a poor predictor of EoE (4-7). Additionally, findings typically suggestive of EoE could be underreported and undetected at the time of food impaction and possibly blamed on trauma related to the impaction itself. The ASGE reports up to 33% of food impactions could be related to EoE (2). The American College of Gastroenterology currently has no recommendations for biopsy at the time of food bolus impaction (11). The ESGE recommends diagnostic work-up including histologic evaluation after extraction of the foreign body (1). However, this recommendation states the work-up could be done at future endoscopy. Given the poor follow-up in these patients, this could further add to the delay in diagnosis and treatment.

Two prior retrospective studies examined EoE in relation to food bolus impaction. Chang et al. examined 220 patients at a tertiary medical center who presented with food bolus impaction; of these, 38.2% were biopsied at the time of impaction, but only 45.5% had documented follow-up. The patients who were and were not lost to follow-up did not show statistically significant differences in demographics. Patients meeting histologic criteria on biopsy were more likely to be lost to follow-up, whereas patients with a PCP were more likely to follow up (8). This study had a higher rate of biopsy but a lower rate of follow-up compared to our cohort data (28% and 49% respectively); however, they classified follow-up in a similar manner as we did. Unlike our study which included all patients (transfers from other hospitals, emergency admissions, and direct admissions), they only analyzed data from patients presenting to the emergency department. A second study by Donohue et al. examined 171 patients with food impaction or suspected EoE. They found 46% were biopsied at the time of esophageal food impaction with 32% lost to follow-up (9). Given the limited published data, our study complements these prior studies and extends their findings by examining follow-up and biopsy data, treatment recommendations, complications, other EGD findings, and successful extraction methods. In particular, we worry that patients who do not receive biopsy at index event could be harmed by delay in diagnosis and management while experiencing future hospitalizations for food impactions and progression of fibrosis of their disease. We found that three out of the 10 patients who presented for subsequent food impaction where later diagnosed with EoE. Furthermore, there were no complications noted in the patients who did receive biopsy.

Our study does have several limitations, including being conducted at a single tertiary care medical center in the southeast United States. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to other regions or medical centers. Comparing the southeast United States (temperate climate zone) as the reference to other climate zones in the United States, there is some reported variability in odds of esophageal eosinophilia with; cold climate zones [odds ratio (OR) =1.39], arid climate zones (OR =1.27, and tropical climate zones (OR =0.87) (12). Patients initially seen at our medical center may have decided to follow up at other healthcare facilities, especially if they were transferred from another healthcare system. Given that our study was a retrospective chart review, we relied on the medical records for accurate histories and endoscopic findings. At our institution, these cases tend to present afterhours and are completed in the OR rather than the endoscopy unit. This could possibly impact and degree of patient interaction and subsequent patient education in regard to follow-up. Our criteria and definition for follow-up was also very broad in an attempt to capture all healthcare interaction. We acknowledge some of these follow-up appointments may not have resulted in significant care or treatment.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with food impaction are at risk for undiagnosed EoE. Many of these patients were not biopsied and may not have had features of EoE which were recognized at the time of food impaction. The majority of patients were recommended for follow-up for future EGD and biopsy however, a large portion never returned. Only around 35% who were given follow-up actually returned. Our analysis is comparable and strengthened by to two previous studies that showed low rates of biopsy and high rates of lost to follow-up when patients present for food bolus impaction. However, we expanded on prior reports by finding that patients who did not receive a biopsy at the initial encounter had higher rates of repeat food impactions (13.9% vs. 0%, P=0.04). These patients were also less likely to be given treatment recommendations (93% vs. 68%, P=0.01), which could increase morbidity of the disease (10). In our study, this led to a delay in EoE diagnosis in 30% of patients who presented for repeat food impaction. Our results suggest that patients presenting for food bolus impaction should receive a biopsy at the time of the initial encounter to rule out underlying disease given poor follow-up. Current guidelines are lacking on this topic. As with many medical conditions, these patients may also benefit from closer surveillance and reminders to increase the likelihood of keeping follow-up appointments.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://aoe.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/aoe-24-1/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://aoe.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/aoe-24-1/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-24-1/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://aoe.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/aoe-24-1/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the institutional ethics board of Wake Forest University Health Sciences IRB00000212 and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, et al. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2016;48:489-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:1085-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiremath G, Vaezi MF, Gupta SK, et al. Management of Esophageal Food Impaction Varies Among Gastroenterologists and Affects Identification of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2018;63:1428-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shoda T, Wen T, Aceves SS, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis endotype classification by molecular, clinical, and histopathological analyses: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:477-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, et al. The prevalence and diagnostic utility of endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:988-96.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie SH, Go M, Chadwick B, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia--a prospective analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1140-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prasad GA, Talley NJ, Romero Y, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2627-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang JW, Olson S, Kim JY, et al. Loss to follow-up after food impaction among patients with and without eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 2019;32:doz056. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donohue S, Hillman L, Lomeli L, et al. 460 High Rates of Loss to Follow-Up After Esophageal Food Impaction in Suspected Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Time to Standardize Care. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:S269. [Crossref]

- Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 2013;145:1230-6.e1-2.

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:679-92; quiz 693. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurrell JM, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia varies by climate zone in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:698-706. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Delaney S, Harris Z, Clayton S. Potential missed opportunities for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of eosinophilic esophagitis: analysis of endoscopic food impaction management. Ann Esophagus 2024;7:11.