A narrative review of current functional assessment of the upper esophageal sphincter

Introduction

Swallowing is a physiological process typically organized in a sequence of events, in which the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) constitutes an important anatomic and functional landmark. Different clinical conditions require the study of this mechanism in its diagnostic investigation. Historically, several diagnostic methods have tried to study this region with little success. The emergence of high-resolution manometry (HRM) allowed an advance in the study of this region and an increase in the diagnostic possibilities of the diseases related to UES.

The aim of this review is to update the concepts regarding the diagnosis of UES disorders. We present the following article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-21-17/rc).

Methods

Information used to write this paper was collected from PubMed with the following keywords: “high-resolution manometry”, “esophageal motility”, “pharynx”, “upper esophageal sphincter” from August 2009 until December 2020. Only articles written in English performed on adult humans were selected for primary review. The references of the articles were manually reviewed for additional relevant papers.

Discussion

UES: morphology and function

For a better understanding of the physiology of normal swallowing, this phenomenon is didactically divided into three phases: oral, pharyngeal and esophageal (1). The first two phases occur in less than 2 s while the third lasts between 10 and 15 s.

The oral phase of swallowing is under mostly voluntary muscle control and involves transit of a prepared bolus beyond the oral cavity. The pharyngeal phase of swallowing follows immediately thereafter. The superior, middle, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles contract in peristaltic series, manipulating the ingested bolus downward. This contraction also facilitates transient relaxation of the cricopharyngeus, the dominant muscle within the UES, to allow bolus passage into the esophagus (1).

Anatomically, UES tends to span 2 to 4 cm in length and is composed beyond the muscle fibers by cartilage and aponeurotic tissue. These characteristics make the UES asymmetrical in its dimensions (axial and radial) and also unique in the fact that its fibers, unlike the distal digestive tract, are striated and present a quick motor response, hinder its formal evaluation (2).

Fundamentally, by contracting, the UES creates an obstacle between the pharynx and the esophagus, thus protecting the airways from the entry of food content and gastroesophageal refluxate (3).

UES: diseases

Swallowing mechanism can be altered by several anatomical and functional changes with different clinical repercussions. Abnormalities of the pharyngeal phase, and in particular of the UES, can be difficult to isolate due to this region’s functional complexity (4). These abnormalities can be didactically grouped into: structural, neurological, rheumatological, infectious and iatrogenic (Table 1).

Table 1

| Structural | Neurological | Rheumatologic | Infectious | Iatrogenic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cricopharyngeal bar | Stroke | Polymyositis | Candidiasis | Radiation |

| Zenker’s diverticulum | Encephalopathy | Sarcoidosis | Herpetic mucositis | Surgery |

| Head and neck tumors | Neurodegenerative disease | Sjogren’s syndrome | ||

| Neuropathy |

UES, upper esophageal sphincter.

UES: when to evaluate

Many clinical scenarios, such as pharyngeal globus, aspiration risk or suspicion of supra-esophageal reflux disease (SERD), may require specific assessment of the UES. The most common symptomatic presentation that requires investigation is the differentiation of oropharyngeal dysphagia from esophageal dysphagia, which are often not differentiable only with clinical data, making it necessary to perform specific tests for diagnostic confirmation (4).

On the other hand, even when the clinical diagnosis of swallowing disorder is possible, diagnostic investigation may be necessary to assess the intensity or progression over time of the disease’s involvement.

UES: how to evaluate

Some imaging diagnostic tests, such as videofluoroscopy or cross-sectional imaging through CT or MRI, or endoscopes through a functional variation of nasopharyngolaryngoscopy are used in the study of UES, all of which however, have important diagnostic limitations due to subjectivity in the interpretation of the findings (4).

In the same way, conventional manometry, for many reasons proved to be an inadequate diagnostic method to study the functional anomalies of the UES. First, it is based on a water perfused system with a response rate to the pressure variations insufficient to properly analyze striated muscle contraction and leading to a constant dripping of water that stimulates the UES. Second, the elevation of the hypolaryngeal complex during swallowing causes motion artifacts. Last, the UES has a radial and longitudinal asymmetry and only four radial sensors may be inappropriate (5).

All of these disadvantages do in fact compromise the results of conventional manometry, which has led in the past, many authors do not recommend the routine use of this test in UES studies.

This scenario changed with the emergence of HRM, which provides better understanding of anatomophysiology of the pharynx and esophagus, since with this new technology there was an increase in the number of sensors and their approximation in the catheter. In addition, a solid-stated catheter started to be used, avoiding the continuous dripping of water in the pharynx during the test, reducing the disadvantages of conventional manometry (6,7).

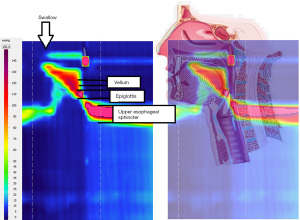

Correct HRM anatomofunctional correlations is already well established through imaging or endoscopy methods (5). HRM allows manometric parameters evaluation within four anatomical regions: the velopharynx, mesopharynx, hypopharynx, and UES (Figure 1).

Maximal and minimal pressures as well as the timing and duration of salient pressure events are recorded. UES occlusive pressures are usually pre- or post-deglutitive measured (8,9).

The development of HRM thus allowed the study of UES not only in swallowing disorders (9,10), but also the repercussion in its contractile function, of other esophageal diseases, such as gastroesophageal reflux (11) or achalasia (12). Recently, new and important applications of HRM are also being found in the practice of speech therapy and laryngology (13-17).

Conclusions

Functional study of UES through HRM has allowed not only a better understanding of its functioning under normal and pathological conditions, but also an increased number of situations in which it can be applied. For this reason, new and continuous clinical research is needed, seeking to increase our knowledge of the possibilities of using HRM in the diagnosis of functional changes in the UES.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Annals of Esophagus for the series “Upper Esophageal Sphincter”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-21-17/rc

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-21-17/coif). The series “Upper Esophageal Sphincter” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. FAMH served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Esophagus from September 2020 to August 2022. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Miller L, Clavé P, Farré R, et al. Physiology of the upper segment, body, and lower segment of the esophagus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1300:261-77. Erratum in: Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014;1325:269. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh S, Hamdy S. The upper oesophageal sphincter. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005;17:3-12. Erratum in: Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005;17:773. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cook IJ, Dodds WJ, Dantas RO, et al. Opening mechanisms of the human upper esophageal sphincter. Am J Physiol 1989;257:G748-59. [PubMed]

- Ahuja NK, Chan WW. Assessing upper esophageal sphincter function in clinical practice: a primer. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2016;18:7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silva LC, Herbella FA, Neves LR, et al. Anatomophysiology of the pharyngo-upper esophageal area in light of high-resolution manometry. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:2033-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox M, Hebbard G, Janiak P, et al. High-resolution manometry predicts the success of oesophageal bolus transport and identifies clinically important abnormalities not detected by conventional manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:533-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cock C, Omari T. Diagnosis of swallowing disorders: how we interpret pharyngeal manometry. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2017;19:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryu JS, Park DH, Kang JY. Application and interpretation of high-resolution manometry for pharyngeal dysphagia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;21:283-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Omari TI, Ciucci M, Gozdzikowska K, et al. High-resolution pharyngeal manometry and impedance: protocols and metrics-recommendations of a High-Resolution Pharyngeal Manometry International Working Group. Dysphagia 2020;35:281-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cock C, Omari T. Systematic review of pharyngeal and esophageal manometry in healthy or dysphagic older persons (>60 years). Geriatrics (Basel) 2018;3:67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nadaleto BF, Herbella FA, Pinna BR, et al. Upper esophageal sphincter motility in gastroesophageal reflux disease in the light of the high-resolution manometry. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menezes MA, Herbella FA, Patti MG. High-resolution manometry evaluation of the pharynx and upper esophageal sphincter motility in patients with achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:1753-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knigge MA, Thibeault S, McCulloch TM. Implementation of high-resolution manometry in the clinical practice of speech language pathology. Dysphagia 2014;29:2-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinna BR, Herbella FAM, de Biase N, et al. High-resolution manometry evaluation of pressures at the pharyngo-upper esophageal area in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia due to vagal paralysis. Dysphagia 2017;32:657-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinna BR, Herbella FAM, de Biase N. Pharyngeal motility in patients submitted to type I thyroplasty. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2021;87:538-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaiano T, Herbella FAM, Behlau M. High-resolution manometry as a tool for biofeedback in vertical laryngeal positioning. J Voice 2021;35:418-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mororó WC, Herbella FA, de Oliveira KVG, et al. Pharyngeal motility before and after thyroarytenoid muscle botulinum toxin injection. Dysphagia 2020;35:806-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Laurino Neto RM, Herbella FAM. A narrative review of current functional assessment of the upper esophageal sphincter. Ann Esophagus 2022;5:29.