Robot-assisted hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis after esophagectomy

Introduction

Locally advanced esophageal cancer is mostly treated by chemo(radio)therapy followed by radical esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy (1). After esophagectomy, a gastric conduit reconstruction with an intrathoracic or cervical anastomosis is usually made. Although extensive efforts have been made to identify the optimal anastomotic technique in esophagectomy, the incidence of anastomotic leakage remains about 15–20% (2). Previous studies comparing hand-sewn versus stapled anastomotic techniques have been inconclusive (3-5).

To construct an intrathoracic anastomosis during esophagectomy, a hand-sewn, linear stapled, or circular stapled technique can be applied (6). With the increasing use of minimally invasive surgery and number of surgeons adopting the Ivor-Lewis approach for mid to distal esophageal tumors, a stapled anastomosis has become the standard of care for conventional minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) (7). However, articulating robotic instruments improve the surgeon’s dexterity and facilitate the construction of a hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis in robot-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy (RAMIE). In our center, this technique was introduced in 2016 and refined during the subsequent years (8). The aim of this study was to describe our current technique and evaluate the outcomes of patients who underwent RAMIE with this type of robot-assisted hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-20-98/rc).

Methods

Patient population

Patients were selected from a prospectively maintained database of the University Medical Center Utrecht. Patients who underwent a RAMIE with an intrathoracic hand-sewn anastomosis between 1 November 2019 and 1 November 2020 were included in the current retrospective study. A hand-sewn anastomosis was standard of care for all patients who underwent Ivor-Lewis. This inclusion period was chosen because the aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of the current anastomotic technique after previously reported refinements (8). This anastomotic technique was uniformly applied throughout the consecutive cases.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethical board of the University Medical Center Utrecht (No. 13-061) and the need for informed consent was waived.

RAMIE procedure

All patients underwent fully robotic RAMIE (i.e., robotic surgery during both the abdominal and thoracic phase) with extended two-field lymphadenectomy (including mediastinal stations 2 and 4), gastric conduit reconstruction with intrathoracic anastomosis. The technical steps of the thoracic phase of the RAMIE procedure were described in detail in a previous publication (9). All surgeries were performed by 2 surgeons who have RAMIE experiences since 2003 and 2011 respectively and perform RAMIE procedures with an intrathoracic hand-sewn anastomosis since 2016 and onwards.

Anastomotic technique

Positioning

For the thoracic phase, the patient was placed in left sided semi-prone position. An 8 mm robotic trocar is inserted in the 6th intercostal space for the camera. The other 3 robotic 8mm trocars were inserted in the 4th, 8th and 10th intercostal space. The assistant port was placed in the 5th intercostal space. For the creation of the intrathoracic anastomosis, robotic arm 1 and 2 were used for the Cadiere and the Vessel Sealer, arm 3 for the camera and arm 4 for the Needle Driver. The assistant port was mainly used for suction and the introduction of sutures.

Location of anastomosis

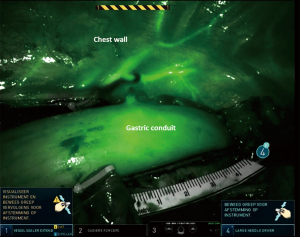

In general, the anastomosis was constructed at the level, just above the azygos vein, guided by tumor location. 7.5 milligram indocyanine green (ICG) was injected and visualized by fluorescence Firefly technology (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) to evaluate the vascularization of the gastric conduit and determine the exact anastomotic site at the gastric conduit (Figure 1).

Incision in gastric conduit

The incision is approximately 1–2 centimeters and made with a Cautery Hook parallel to the longitudinal gastric stapler line. The location in relative to this staple line is halfway in the gastric conduit, slightly near the omentum.

Supportive stitches

In order to create an adequate overview of the serosa of the esophagus, 4 supportive stay-stiches were placed in the wall of the esophagus using a Vicryl 4.0.

Suturing anastomotic wall

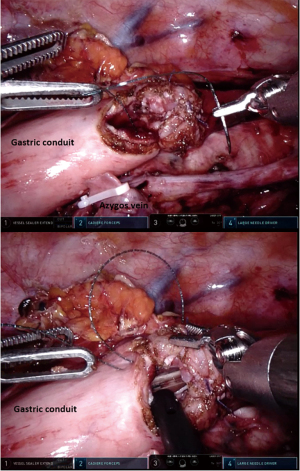

The anastomosis was performed with an end-to-side construction (Figure 2). A barbed V-Loc 4.0 suture was used to close the posterior wall by a single-layer running hand-sewn technique. The space between the bites was aimed to be around 5mm. In a similar way, the anterior wall was sutured with a separate barbed V-Loc 4.0. When the anastomosis was almost closed, a nasogastric tube was inserted and positioned under vision. The sutures were secured by sewing the V-Loc in backward direction.

Tension release stitches

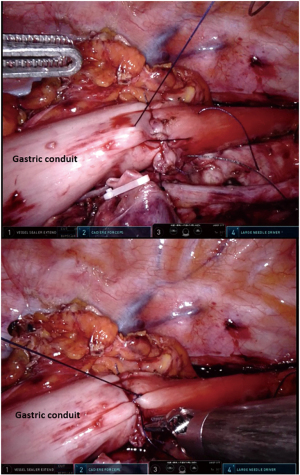

To avoid traction on the running sutures of the anastomosis, 3–4 tension releasing mattress stitches were placed as an overlay to approximate the esophageal wall to the gastric wall (Figure 3). For this step a Vicryl 3-0 suture was used.

Omental wrap

In all cases an omental wrap was applied. To avoid possible twisting of the gastric conduit, this was not performed in a circular fashion, instead the omentum was only fixed on the anterior wall of the anastomosis. Care was taken to position the gastric conduit in the esophageal bed.

Perioperative management

An enhanced recovery after esophagectomy protocol was used for the postoperative management and did not change during the inclusion period. Generally, all patients received epidural or paravertebral anesthesia. The epidural or paravertebral catheter was removed on postoperative day 3. During surgery, 2 Jackson Pratt drains were inserted bilateral in the thoracic cavity. Only if indicated a large caliber thoracic drain was left behind (i.e., pulmonary damage). The Jackson Pratt drains were usually removed when the production was less than 200 milliliters per 24 hours. The nasogastric tube remained until the contrast imagine was performed at postoperative day 4. The aim of this contrast imagine is to look for delayed gastric emptying and vocal cord dysfunction or aspiration. If this was not the case, the nasogastric tube was removed at postoperative day 4 and the patient could start with water intake. A jejunostomy feeding tube was routinely placed, as oral intake was prohibited until postoperative day 4 and carefully resumed from then onward.

Outcomes

All outcomes were extracted from a prospectively maintained database. The primary outcome was anastomotic leakage defined by the Esophageal Complications Consensus Group (10). Secondary outcomes were length of hospital stay, in-hospital mortality and duration of the anastomosis. The total duration of the anastomosis was defined as the time (minutes) between the incision in the gastric conduit and the omental wrap. The duration of the anastomosis walls was defined as the time (minutes). between the first suture of the posterior wall and the last suture of the anterior wall. All operations were routinely recorded and stored at the hospital server, hence it was possible to review the surgical videos and determine the exact duration of the anastomosis.

Statistics

Data was analyzed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM). Only descriptive analyses were performed. Continuous outcomes were shown as a median with range or mean with standard deviation, depending on data distribution. Categorical data were shown as numbers with percentages.

Results

Between November 2019 and November 2020, 22 consecutive patients who underwent RAMIE with an intrathoracic hand-sewn anastomosis were included. The patient characteristics and outcomes are shown in Table 1. The total time to complete the anastomosis, measured from the incision in the gastric conduit until the omental wrap was finished, was a median of 37 minutes (range, 25–48 minutes). Closing the posterior and anterior wall took a median of 23 minutes (range, 16–32 minutes). Out of 21 patients, 3 patients developed anastomotic leakage (14%). These cases involved a grade I leak in 2 patients (9%) and a grade III leak in 1 patient (5%). A Grade 1 leak was treated with antibiotics and nil per mouth. The patient with a grade III leak required a reoperation. In-hospital mortality occurred in 1 patient (5%), which was caused by massive aspiration. The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (6-20).

Table 1

| Variables | Number |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Age, years | 66 [39–81] |

| ASA classification | |

| 2 | 11 (50%) |

| 3 | 11 (50%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Distal | 16 (73%) |

| Mid | 1 (5%) |

| Junction | 5 (22%) |

| T stadium | |

| T1b | 1 (5%) |

| T2 | 3 (14%) |

| T3 | 17 (77%) |

| T4a | 1 (5%) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 20 (91%) |

| Chemotherapy | 1 (5%) |

| None | 1 (5%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Radicality | |

| R0 | 22 (100%) |

| Lymph node yield | 46 [27–72] |

| Duration of anastomosis, minutes | |

| Posterior and anterior wall | 23 [16–32] |

| Total* | 37 [25–48] |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 (14%) |

| Grade I | 2 |

| Grade II | – |

| Grade III | 1 |

| Mortality | 1 (5%) |

| Duration of hospital stay, days | 9 [6–20] |

*, from incision in gastric conduit till the omental wrap was finished.

Discussion

This study described the current technique of an intrathoracic hand-sewn anastomosis in RAMIE, which was developed in our center. After several years of refining the technique, an anastomotic leakage rate of 14% was observed in our most recent case series. Hence, the currently presented technique seems safe and reliable to construct an intrathoracic anastomosis in RAMIE.

The incidence of anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy varies widely in literature, with the general range being 10–30% (2,11). Nonetheless, recent multicenter studies suggest that an anastomotic leakage rate of 10–20% is realistic for expert centers (2,12,13). A recent multicenter study by the Upper GI International Robotic Association (UGIRA), which investigated the outcomes of 856 RAMIE procedures in 20 international centers, reported an overall anastomotic leakage rate of 20% (14). In that cohort, a 33% anastomotic leakage rate in a subgroup of 151 patients who received an intrathoracic robot-assisted hand-sewn anastomosis was observed. These initial data come mainly from centers in their learning curve of the technique. However, more recently most UGIRA centers switched to a stapled anastomotic technique because of unsatisfying initial outcomes with a hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis in RAMIE. It should be noted that an initial anastomotic leakage rate of up to 30% was also observed for intrathoracic stapled anastomosis in a multicenter study that investigated the learning curve of surgeons switching from a cervical technique, which decreased to 8% after 119 cases (13). The results from our previous study and current series show that the learning curve of a robot-assisted hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis may be comparable and yields acceptable outcomes, with an anastomotic leakage rate of 14% in our latest series, of which only one patient required a re-operation (13).

The hand-sewn robot-assisted anastomosis has several benefits. Foremost, the currently presented technique allows the construction of a fully robotic intrathoracic anastomosis, which does not require the surgeon to step away from the console to the table for the introduction of a circular stapling device through a mini-thoracotomy. The hand-sewn approach does not necessitate the presence of an experienced bedside assistant for the construction of the anastomosis which contributes to the surgeons’ autonomy. Furthermore, a hand-sewn anastomosis allows the surgeon to construct a tailored anastomosis which can be easily adapted to the individual patient, particularly in terms of the anastomotic site, size and the ensuing tension on the anastomosis. Although a hand-sewn anastomosis is harder to standardize than the (semi-)mechanical alternatives, increased control may provide benefits in the hands of an experienced surgeon.

Few studies published in detail on the technique of a robot-assisted hand-sewn anastomosis during RAMIE (15-19) (Table 2). Although the techniques differ substantially, the importance of several technical factors are highlighted universally. One of these factors is the distance between the incision in the gastric conduit and the longitudinal stapler line (16,18). Relative ischemia is an important risk factor for anastomotic leakage, which presumably occurs more often in the tissue directly adjacent to the longitudinal staple line and in the gastric conduit tip (20). The anastomotic site should therefore be selected carefully in order to facilitate creation of the anastomosis in a well vascularized region, possibly aided by fluorescence imaging. Another potentially relevant, yet subjective, factor is the tension on the anastomosis. If the gastric conduit is too elongated and anastomosed without any tension on the anastomosis, a dilated gastric conduit suffering from delayed gastric conduit emptying could be the consequence. On the other hand, if tension on the anastomosis is too high, the tissue might tear resulting in anastomotic leakage. This balance might be found more easily in a hand-sewn anastomosis.

Table 2

| Study | Year | Patients (n) | Technique | Anastomotic leakage rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerfolio et al. (18) | 2013 | 16 | Double layer, end-to-side | 0 (0%) |

| Trugeda et al. (17) | 2014 | 14 | Double layer, end-to-end | 4 (29%) |

| Bongiolatti et al. (16) | 2016 | 8 | Single layer, end-to-side | 2 (25%) |

| Egberts et al. (15) | 2017 | 52 | Double layer, end-to-end | 5 (10%) |

| Zhang et al. (19) | 2018 | 26 | Double layer, end-to-end | 2 (8%) |

The success of an anastomotic technique is multifactorial making every detail count. However, we consider several refinements as essential contributors to the current technique. Firstly, using tension releasing stitches appears to lead to the right balance of tension on the anastomosis. Secondly, the vascularization of the anastomosis is of importance. Factors such as location in the gastric conduit and type of suture (V-Loc 4.0) have furthermore contributed to our anastomotic technique.

In conclusion, the currently presented technique for robot-assisted hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis is safe and feasible for achieving an anastomotic leakage rate of 14% in our most recent cohort of patients who underwent RAMIE. In our experience, the most important technical aspects include the location of the anastomosis and the right balance of tension on the anastomosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Alejandro Nieponice) for the series “Anastomotic Techniques for Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy and Endoscopic Handling of Its Complications” published in Annals of Esophagus. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-20-98/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-20-98/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-20-98/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://aoe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aoe-20-98/coif). The series “Anastomotic Techniques for Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy and Endoscopic Handling of Its Complications” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. RvH and JPR report that they are proctors for Intuitive Surgical Inc. and are consultants for Medtronic. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethical board of the University Medical Center Utrecht (No. 13-061) and the need for informed consent was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1090-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Kuppusamy MK, Alderson D, et al. Benchmarking Complications Associated with Esophagectomy. Ann Surg 2019;269:291-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Vyas S, et al. Hand-sewn versus stapled oesophago-gastric anastomosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:876-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu QX, Min JX, Deng XF, et al. Is hand sewing comparable with stapling for anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy? A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:17218-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markar SR, Arya S, Karthikesalingam A, et al. Technical factors that affect anastomotic integrity following esophagectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:4274-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Plat VD, Stam WT, Schoonmade LJ, et al. Implementation of robot-assisted Ivor Lewis procedure: Robotic hand-sewn, linear or circular technique? Am J Surg 2020;220:62-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haverkamp L, Seesing MF, Ruurda JP, et al. Worldwide trends in surgical techniques in the treatment of esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-7. [PubMed]

- de Groot EM, Möller T, Kingma BF, et al. Technical details of the hand-sewn and circular-stapled anastomosis in robot-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus 2020;33:doaa055.

- van der Sluis PC, van der Horst S, May AM, et al. Robot-assisted Minimally Invasive Thoracolaparoscopic Esophagectomy Versus Open Transthoracic Esophagectomy for Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg 2019;269:621-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, et al. International Consensus on Standardization of Data Collection for Complications Associated With Esophagectomy: Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group (ECCG). Ann Surg 2015;262:286-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biere SS, Maas KW, Cuesta MA, et al. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Surg 2011;28:29-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt HM, Gisbertz SS, Moons J, et al. Defining Benchmarks for Transthoracic Esophagectomy: A Multicenter Analysis of Total Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy in Low Risk Patients. Ann Surg 2017;266:814-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Workum F, Stenstra MHBC, Berkelmans GHK, et al. Learning Curve and Associated Morbidity of Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Ann Surg 2019;269:88-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kingma BF, Grimminger PP, van der Sluis PC, et al. Worldwide Techniques and Outcomes in Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy (RAMIE): Results from the Multicenter International Registry. Ann Surg 2020; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Egberts JH, Stein H, Aselmann H, et al. Fully robotic da Vinci Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy in four-arm technique-problems and solutions. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bongiolatti S, Annecchiarico M, Di Marino M, et al. Robot-sewn Ivor-Lewis anastomosis: preliminary experience and technical details. Int J Med Robot 2016;12:421-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trugeda S, Fernández-Díaz MJ, Rodríguez-Sanjuán JC, et al. Initial results of robot-assisted Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy with intrathoracic hand-sewn anastomosis in the prone position. Int J Med Robot 2014;10:397-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Hawn MT. Technical aspects and early results of robotic esophagectomy with chest anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:90-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Xiang J, Han Y, et al. Initial experience of robot-assisted Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy: 61 consecutive cases from a single Chinese institution. Dis Esophagus 2018; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myers CJ, Mutafyan G, Pryor AD, et al. Mucosal and serosal changes after gastric stapling determined by a new "real-time" surface tissue oxygenation probe: a pilot study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:50-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: de Groot EM, Kingma FB, Goense L, van der Horst S, van den Berg JW, van Hillegersberg R, Ruurda JP. Robot-assisted hand-sewn intrathoracic anastomosis after esophagectomy. Ann Esophagus 2022;5:19.