食管切除术后实施标准化临床路径的早期布局、临床获益和局限性

引言

食管癌是全世界死亡率第六的恶性肿瘤,近年来食管癌的发病率基本稳定。来自亚洲的数据显示,食管癌发病率已达到峰值,每年新增病例超过400 000例,与西方国家近年来报道的发病率基本稳定相似[1]。美国的食管癌发病率和死亡率近几年趋于平稳,但在过去十年中略有下降,这可能与Barrett’s食管监测项目有关。发病率的变化也与5年总生存率的提高有关,所有癌症的生存率从20世纪60~70年代的约5%提高到目前的20%[2]。

随着时间的推移,这些变化的原因是多方面的。可能包括筛查项目及内窥镜和外科治疗的进步。当前局限期食管癌的治疗以多学科治疗为核心,这是一种更全面和系统的方法,有助于改善局部晚期食管癌(T2~3,N0~3,M0)的生存结果。

虽然食管癌术后复发率和死亡率均较高,但食管切除术一直是公认的可能到达肿瘤根治的基础。然而,新疗法及技术的改进有助于降低食管切除术后的复发率。Biere等人进行了一项多中心、随机对照试验,评估了较大医学中心(>30例食管切除术/年)里开放和微创手术都有丰富经验的外科医生,应用微创手术后肺部并发症的发生率明显下降[3]。同样地,在过去几十年中,食管切除术后的死亡率也逐渐下降,从10%~15%下降到最近报告的术后90天内死亡率低至4.5%[4,5]。由于缺乏标准化的评估系统,围手术期并发症的发生率以前很少被量化。最近,随着食管术后并发症共识专家组(ECCG)的成立,这种情况得到了改善,ECCG报道显示当前国际上围手术期并发症发生率为59%[5]。

该手术的复杂性在于涉及胸部和腹部两个区域,需要繁琐的手术重建,这些因素都与短期和长期的副作用相关。此外,食管癌患者通常表现为营养不良,并伴有与其高龄相关的基础疾病。这些复杂性引起了很多国家的重视,并启动了多学科综合高危癌症患者护理项目,使其得到了一定程度解决。尽管美国尚未启动多学科综合癌症护理计划,但许多研究已经证明,在较大医学中心进行治疗有助于改善预后[4,6]。

外科围手术期结果的衡量和评价需要有能被普遍接受的评估结果和质量控制的标准化系统,该评价系统在2015年由ECCG报道完成[7]。随着时间的推移,标准化临床路径(SCPs)和加速康复外科(ERAS)指南的开发和应用也对结果产生了积极的影响,从而使患者获得了标准化的诊疗路径和目标。这些路径也兼顾了外科技术和多种诊疗模式的发展。既往已经证明SCPs会显著降低围手术期死亡率(<1%),住院时间(LOS)降低至7~9天[8,9]。这些SCPs也被证明可以被应用于其他大的医学中心[10]。标准化围手术期路径的目的旨在减少手术并发症并加速康复[11]。

ERAS协会开发了标准化临床路径应用的最佳国际范例,该范例为围手术期阶段提供了清晰和标准化的方法,如术前准备和术前检查、术中/术后管理和基础设施,以避免并发症并加速患者康复。ERAS指南已被结直肠外科广泛接受,并扩展到其他外科领域,如胃切除术、减重手术、肝脏手术和妇科肿瘤。食管切除术的ERAS指南于2019年2月发布[12],利用了其他学科已得到验证的许多ERAS指南概念,扩展了其应用的范围,使其涵盖了食管切除这个特有的疾病领域。

本文旨在回顾当前相关文献,评估SCPs和ERAS对食管切除术预后的影响,并评估目前在较大医学中心的应用水平。

方法

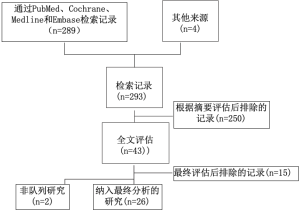

通过PubMed、Embase、Medline和Cochrane数据库搜索引擎进行文献检索,以筛选相关研究。仅纳入比较研究、随机对照试验(RCT)以及前瞻性和回顾性队列研究,基于以下检索术语和关键词进行检索:“Esophagectomy”[Mesh],“Esophageal Neoplasms”[Mesh],“Critical Pathways”[Mesh],“Evidence-Based Medicine”[Mesh], “Evidence-Based Practice”[Mesh],Enhanced Recovery(or“Enhanced Recovery”),Fast Track (or Fast-Track or “Fast Track” or “Fast-Track”)。其他纳入标准也包括无论是否使用了ERAS或非ERAS方案,但分析了食管手术中SCP结果的英文文章。排除非食管手术或缺乏围手术期结果的相关研究。所有符合条件的文章根据其主要术后结果进行分析和分类:术后复发率和并发症发生率、住院时间和围手术期死亡率。所有被纳入的文章也进行了评估,以提取更多感兴趣的变量,如营养状况、住院费用和SCP描述,这些结果可能也包含在统计分析中。

结果

共检索出289篇文献(图1)。通过初步的摘要评估及排除非英文献,250项研究被剔除。经过全面的全文评估,结果纳入了26篇一共包含3 721名患者的合格文章[8,10,13-36]。所有文献均包括患者接受了食管切除术,采用了多种手术方法包括经食管裂孔、左开胸、两切口或三切口手术、微创或开放技术。所有26篇文章都是比较研究(其中5篇RCT,6篇前瞻性试验),并报告了与SCP或ERAS项目应用相关的结果。关于主要结果的信息在纳入的研究中差异很大,而患者营养状况和住院费用数据的收集不足,无法进行彻底的分析。

ERAS项目和审查条款议定书

最近发布了正式的ERAS建议,收集了所有相关的围手术期项目,并首次引入了一些严格适用于食管切除术的组成部分。新模块包括食管切除术的特殊组成部分(如术前营养评估和治疗、术前口服营养药物及多学科肿瘤委员会的介入和康复计划)。手术部分(新辅助治疗后的手术时机、导管的选择、幽门成形术和淋巴结切除术的范围、吻合口周围或胸腔引流管的使用、NG管和肠内营养导管、麻醉过程中的液体和通气管理)。然而大多数入组的文章回顾了他们SCP机构版本的结果,导致了机构协议中的各种元素和结果评估的不一致性。

术后结果

住院时间

24项研究中报道了3,626名患者的住院时间数据。SCP组的平均住院时间(9.9±2.8)明显低于对照组(13.4±1.0),差异有统计学意义(P<0.001)。对再次入院率也进行了分析,发现两组之间相似(P=0.739)。

术后并发症发生率

19项研究报道了并发症发生率,分别比较了SCP组和传统组中的1 129和962名患者。总并发症发生率分别为29.8%和32.5%,尽管两组比较没有统计学意义(P=0.350),但分析也显示出SCP组的有更好的预后。

术后死亡率

17项研究记录了2 661名患者住院期间死亡率和术后90天死亡率的综合结果。SCP组的总体死亡率为2.2%,传统治疗方法组患者死亡率为2.9%。差异没有统计学意义(P=0.982)。

吻合口瘘

分析了入组数据集的具体并发症情况,19项研究(总共3,010名患者)报告了组间吻合口瘘的发生率:SCP组和传统组的发生率分别为8.3%和10.3%,两组数据之间没有统计学意义(P=0.659)。

肺部并发症

包含2 509名患者的17项研究报告了肺部并发症的发生情况。SCP组肺部并发症发生率为17.0%,传统组为22.4%。分析表明,SCP的实施与肺部并发症发生率降低有相关性(P=0.011)。

讨论

由于并发症发生率和死亡率较高,食管切除术一直在所有的肿瘤手术中较为特殊。SCPs和最近的ERAS指南被广泛接受,成为改善食管切除术预后的有效方法。本文分析表明,食管切除术后SCP的应用具有降低食管切除术后平均住院日、并发症发生率和死亡率的潜在作用。此外,SCP的实施可以降低肺部并发症的发生率,具有统计学意义,肺部并发症的降低一直是一个重要的术后并发症评估参数[37]。这些数据支持SCPs对围手术期预后有积极影响的结论。虽然这些结果仅报道了初步结论,但随着越来越多的中心启动了个体化版本的SCPs和ERAS指南,外科文献中临床报道正在增加。

启动这些项目的障碍包括资源不足、抗拒变革和员工培训。在此之前,还没有一个标准化的流程使得医学中心根据他们的认知和可用的资源引入SCP。最近出版的食管切除术ERAS指南为患者量较大的中心提供了一种结构化的方法,为希望启动或扩大其ERAS项目的中心进行基础设施建设提供了标准化的依据。

一旦启动了SCPs或ERAS计划,就需要对关键路径目标进行定期审查,以确保遵守和维护ERAS准则。当不遵守和偏离关键目标被发现时,它就可以被处理。SCPs和ERAS项目长期维护的最大弱点是多学科团队关键领域的人员流动。必须对此进行监控,持续的指导和教育是项目成果的基础组成部分。

项目成功实施的最大障碍是关键人员不愿意按照计划修改他们既往的方法,并在SCP或ERAS项目中采用新技术。以前的文章也报道了由于不愿意采用这些工作实践而产生的抗拒改变现象。

本综述证实了采用SCP和ERAS方案,对于规范接受食管切除术患者围手术期管理有潜在的临床获益,然而,本文也存在某些固有的局限性。本文涉及到应用不同的方法处理ERAS和SCPs的各种经验的回顾,不可避免地导致所入组的研究之间和研究本身存在异质性,可能会影响分析的结论。例如,大多数纳入的试验侧重于非特异性手术后的结果,而其中只有5项研究(3项前瞻性和2项回顾性)根据手术类型严格筛选患者(3项研究采用的是开放Ivor Lewis,1项左开胸和1项微创三野食管切除术)。进一步的异质性是由于在所有报告中应用了不同的SCP组成部分。这些不同之处源于对所有方案的审查,凸显了SCPs和ERAS方案目标之间的当前差异。

另一个可能的偏倚是大多数研究对于术后并发症的定义不明确,这些并发症通常是根据个人定义进行报道的,而不是像ECCG公布的那样以标准化的方式报道[7]。然而,现有文献的综述也明确地证实了SCPs和ERAS对预后的重要积极影响。

总之,SCP或ERAS在食管手术中的应用已被证明在术后结果方面具有可衡量的临床优势,如降低并发症发生率和显著缩短的住院时间。然而,仍需要有更多的研究专门关注当前食管切除术后的ERAS指南,并评估在大样本临床中心环境下推行这些方案的长期可行性。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Fernando A. M. Herbella, Rafael Laurino Neto and Rafael C. Katayama) for the series “How Can We Improve Outcomes for Esophageal Cancer?” published in Annals of Esophagus. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoe.2020.02.06). The series “How Can We Improve Outcomes for Esophageal Cancer?” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. CI5: Cancer incidence in five continents. Available online: http://ci5.iarc.fr/Default.aspx

- NIH. Cancer stat facts: esophageal cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html. Accessed on Jan 2019.

- Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1887-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg 2014;260:244-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Kuppusamy MK, Alderson D, et al. Benchmarking complications associated with esophagectomy. Ann Surg 2019;269:291-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munasinghe A, Markar SR, Mamidanna R, et al. Is it time to centralize high-risk cancer care in the United States? Comparison of outcomes of esophagectomy between England and the United States. Ann Surg 2015;262:79-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, et al. International Consensus on standardization of data collection for complications associated with esophagectomy: Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group (ECCG). Ann Surg 2015;262:286-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markar SR, Schmidt H, Kunz S, et al. Evolution of standardized clinical pathways: refining multidisciplinary care and process to improve outcomes of the surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:1238-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Kunz S, Schembre D, et al. Esophagectomy--it's not just about mortality anymore: standardized perioperative clinical pathways improve outcomes in patients with esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1395-402; discussion 402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Preston SR, Markar SR, Baker CR, et al. Impact of a multidisciplinary standardized clinical pathway on perioperative outcomes in patients with oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg 2013;100:105-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:292-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Allum W, De Manzoni G, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in esophagectomy: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS((R))) Society Recommendations. World J Surg 2019;43:299-330. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Zong L, Xu B, et al. Observation of clinical efficacy of application of enhanced recovery after surgery in perioperative period on esophageal carcinoma patients. J BUON 2018;23:150-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi H, Sasaki T, Fujita H, et al. Effects of goal-directed fluid therapy on enhanced postoperative recovery: an interventional comparative observational study with a historical control group on oesophagectomy combined with ERAS program. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2018;23:184-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akiyama Y, Iwaya T, Endo F, et al. Effectiveness of intervention with a perioperative multidisciplinary support team for radical esophagectomy. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:3733-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giacopuzzi S, Weindelmayer J, Treppiedi E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer: a single center experience. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooke DT, Calhoun RF, Kuderer V, et al. A defined esophagectomy perioperative clinical care process can improve outcomes and costs. Am Surg 2017;83:103-11. [PubMed]

- Li W, Zheng B, Zhang S, et al. Feasibility and outcomes of modified enhanced recovery after surgery for nursing management of aged patients undergoing esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:5212-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raman V, Kaiser LR, Erkmen CP. Clinical pathway for esophagectomy improves perioperative nutrition. Healthc (Amst) 2016;4:166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Sun L, Lang Y, et al. Fast-track surgery improves postoperative clinical recovery and cellular and humoral immunity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer 2016;16:449. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karran A, Wheat J, Chan D, et al. Propensity score analysis of an enhanced recovery programme in upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery. World J Surg 2016;40:1645-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gatenby PA, Shaw C, Hine C, et al. Retrospective cohort study of an enhanced recovery programme in oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015;97:502-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang JY, Hong X, Chen GH, et al. Clinical application of the fast track surgery model based on preoperative nutritional risk screening in patients with esophageal cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2015;24:206-11. [PubMed]

- Bhandari R, Hao YY. Implementation and effectiveness of early chest tube removal during an enhanced recovery programme after oesophago-gastrectomy. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2015;53:24-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shewale JB, Correa AM, Baker CM, et al. Impact of a fast-track esophagectomy protocol on esophageal cancer patient outcomes and hospital charges. Ann Surg 2015;261:1114-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan H, Hu X, Yu Z, et al. Use of a fast-track surgery protocol on patients undergoing minimally invasive oesophagectomy: preliminary results. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19:441-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Findlay JM, Tustian E, Millo J, et al. The effect of formalizing enhanced recovery after esophagectomy with a protocol. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:567-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ford SJ, Adams D, Dudnikov S, et al. The implementation and effectiveness of an enhanced recovery programme after oesophago-gastrectomy: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2014;12:320-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao G, Cao S, Cui J. Fast-track surgery improves postoperative clinical recovery and reduces postoperative insulin resistance after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:351-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang J, Humes DJ, Gemmil E, et al. Reduction in length of stay for patients undergoing oesophageal and gastric resections with implementation of enhanced recovery packages. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013;95:323-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blom RL, van Heijl M, Bemelman WA, et al. Initial experiences of an enhanced recovery protocol in esophageal surgery. World J Surg 2013;37:2372-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Ferri LE, Mulder DS, et al. An enhanced recovery pathway decreases duration of stay after esophagectomy. Surgery 2012;152:606-14; discussion 14-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao S, Zhao G, Cui J, et al. Fast-track rehabilitation program and conventional care after esophagectomy: a retrospective controlled cohort study. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:707-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munitiz V, Martinez-de-Haro LF, Ortiz A, et al. Effectiveness of a written clinical pathway for enhanced recovery after transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2010;97:714-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tomaszek SC, Cassivi SD, Allen MS, et al. An alternative postoperative pathway reduces length of hospitalisation following oesophagectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:807-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zehr KJ, Dawson PB, Yang SC, et al. Standardized clinical care pathways for major thoracic cases reduce hospital costs. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:914-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

曲金荣

主任医师,博士,郑州大学博士研究生导师、国际研究生导师,哈佛医学院访问学者,放射科副主任。中华放射学会青年委员、中华放射学会腹部学组委员、中国抗癌协会肿瘤影像专业委员会委员、河南省抗癌协会肿瘤影像专业委员会副主任委员、河南省医学会放射学专科分会常务委员等职。河南省学术技术带头人、河南省青年科技人才奖、首批河南省高层次人才,获得国家自然科学基金面上项目、省厅级等课题多项,省厅级成果奖多项。国际上率先使用MRI对食管癌进行研究及对小肝癌的早期诊断等,培养的研究生发表SCI文章数十篇并多次被国际会议接收为口头报告,相关食管MRI研究被2020版中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)食管癌诊疗指南首次加入并引用。(更新时间:2021/7/30)

闵先军

中国航天科工集团七三一医院。胸外科副主任、外科第三党支部书记。师从王俊院士和李辉教授,曾四次登上国际胸外科专业顶级大会的舞台(14th WCLC、50th STS、13th ISSS 和2020年ASCO年会);曾获得北京市海淀区“知识型职工标兵”、北京市海淀区“学习之星”、“首都市民学习之星”等荣誉称号。(更新时间:2021/7/30)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Puccetti F, Kuppusamy MK, Hubka M, Low DE. Early distribution, clinical benefits, and limits of the implementation of the standardized clinical pathway following esophagectomy. Ann Esophagus 2020;3:7.