Chronic pharyngitis and the association with pepsin detection and reflux disease

Introduction

Chronic pharyngitis is more than just a ‘sore throat’; it causes the patient long-term pain and can even lead to throat erosion and cancer (1). A survey by National Ambulatory Medical Care 1995 showed 4.3% of outpatient healthcare appointments were due to symptoms of pharyngitis, making it the 3rd most common complaint (2). Pharyngitis can occur from a multitude of factors; viral infection being the most common cause, however some bacterial infections are often more serious (2). Typical chronic pharyngitis symptoms include inflammation of the pharyngeal mucosa (3).

Gastroesophageal reflux causes pepsin to reach the throat. Therefore, pepsin has been proposed as a biomarker of gastroesophageal reflux disease, and as a major etiological factor in laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). Pepsin is used in the stomach to break-down protein; the stomach itself is not digested because of a protective mucus layer. However, during a reflux episode, pepsin and stomach acid reaching the oesophagus or throat can cause tissue erosion and inflammation. One method of inflammation was reported where pepsin induced the production of pro-inflammatory factors on the tonsil (4). They argued that inflammation can be caused directly through tissue injury or by antigenic detection of pepsin, leading to the recruitment of lymphocytes. Throat infection and pharyngitis can also occur because pepsin disturbs commensal bacteria lining the throat, allowing pathogenic bacteria to accumulate (5). It is therefore important to clarify the cause of chronic pharyngitis in patients who have been cleared of bacterial, viral and fungal infections to offer optimal therapy.

Previously, the absence of any easy-to-use objective method has hindered the efforts from clinicians and researchers to prove the possible association between reflux and chronic pharyngitis. However, PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited, Cottingham, UK) which is a non-invasive and rapid test for diagnosing the presence of salivary pepsin in clinical samples and used as a biomarker for detecting reflux disease has recently become available and has been used in the present study. Patients provided saliva samples at specific time points because changes in activity can influence the occurrence of reflux episodes. Samples from patients were collected in the morning on waking, the second sample post-prandial 60 minutes after finishing a meal and the third sample within 15 minutes of a symptom. A healthy control group without reflux disease were tested for pepsin concentration in post-prandial saliva samples. These samples were compared to the post-prandial samples in the patient group. Currently, an acceptable concentration of pepsin concentration found in the saliva of a healthy individual in the UK is <75 ng/mL, which is considered as a physiological pepsin concentration. Those which have >75 ng/mL pepsin in saliva samples are pathologically positive and would be classed as diseased and would require medical attention. The cut-off value of 76 ng/mL is in line with the specificity and sensitivity of guides obtained and previously reported (6).

The aim of the present study was to establish the association between reflux and chronic pharyngitis patients. The study would also help to evaluate the diagnostic value of PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) for reflux diseases.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-two patients presenting with typical chronic pharyngitis symptoms and laryngoscopy findings indicating chronic pharyngitis were recruited from the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) outpatient clinic at Jinling Hospital and BenQ Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Patient’s lifestyles were also considered. No significant association was found between patients with pepsin concentrations >75 ng/mL and habits such as; smoking, drinking nor having an appetite for spicy food. Those patients were also assessed by reflux questionnaires, reflux finding score (RFS) (7), reflux symptom index (RSI) (8), and reflux disease questionnaire (RDQ) (9,10). Demographic information of patients with chronic pharyngitis is presented in Table 1, where 18 out of 32 patients completed this information. A control group of similar demographics to the patient group was used for comparison of pepsin concentration. The control group was comprised of 31 healthy individuals recruited from the Department of Gastroenterology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. A comparison of demographics between the control group and patient group is shown in Table 2.

Table 1

| Parameter | All (n=18) | Male (n=7) | Female (n=11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean height (cm) | 164 | 171 | 160 |

| Mean age (years) | 43 | 38 | 46 |

| Mean weight (kg) | 61.8 | 66.4 | 58.8 |

| Smoking habit (%) | 11 | 29 | 0 |

| Drinking habit (%) | 11 | 14 | 14 |

| Appetite for spicy food (%) | 50 | 14 | 72 |

A total of 18 out of 32 patients completed demographic information.

Table 2

| Parameter | Chronic pharyngitis | Control subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 32 | 31 |

| Male/female | 14/18 | 15/16 |

| Age range (years) | 21–64 | 26–68 |

| Mean age (years) | 43 | 45 |

| Failed to provide information | 12 | 0 |

Salivary pepsin collection

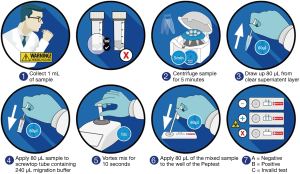

Patients provided saliva which was collected into tubes containing 0.5 mL of 0.01 M citric acid. Each patient provided three salivary samples at specific time points, patients were also informed not to take any medication during the study period. The sample collection and analysis procedure are outlined in Figure 1. One sample was provided in the morning on waking, the second sample post-prandial 60 minutes after finishing a meal and the third sample within 15 minutes of experiencing a symptom. The healthy control group provided only post-prandial samples. All the saliva samples were analysed for the presence of pepsin using PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited). Samples were refrigerated at 4 °C and analysed within 2 days of collection.

Questionnaire

To aid the diagnosis of the cause of the patients’ chronic pharyngitis, patients completed three reflux questionnaires which describe typical reflux symptoms (Table 3). The RFS is a clinician-rated endoscopic finding score based on findings from laryngoscopy (7) which were calculated by rating reflux symptoms to their corresponding number and finding the total (0 to 26), RFS >5 suggests abnormality. The RSI is a self-administered survey based on 9 questions and calculated by rating reflux symptoms from 0 to 5 and finding the total (0 to 45) (8). RSI >13 suggests abnormality. And, the RDQ is a self-rated symptom score (9-11) calculated by rating reflux symptoms such as heartburn, dyspepsia and regurgitation within a time frame, scored from 0 to 5 and used as a classic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) diagnostic tool not considered suitable for the diagnosis of LPR. Patients experience worse symptoms if a higher RDQ total is recorded with a cut-off point of 12 for GERD diagnosis.

Table 3

| Questionnaire | Mean pepsin concentration (ng/mL) ± SD* |

|---|---|

| RSI positive >13 (n=9) | 235±149 |

| RSI negative ≤13 (n=23) | 208±165 |

| RFS positive >5 (n=17) | 176±150 |

| RFS negative ≤5 (n=15) | 261±161 |

| RSI and RFS positive (n=7) | 187±119 |

| RSI and RFS negative (n=13) | 239±158 |

*, mean pepsin concentration was calculated from the sample provided with the highest concentration of pepsin. RSI, reflux symptom index; RFS, reflux finding score.

Analysis

Collection tubes were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min and a clear supernatant was seen. Samples were centrifuged again if no supernatant was observed. 80 µL of clear supernatant was drawn up into an automated pipette. The 80 µL sample was transferred to a screw-top microtube containing 240 µL of migration buffer solution. This sample was mixed with a vortex mixer for 10 s. A second pipette was used to transfer 80 µL of the sample to the circular well of a lateral flow device (LFD) containing two unique human monoclonal antibodies; one to detect and one to capture pepsin in the saliva sample (PeptestTM, RD Biomed Limited) (Figure 1). The lower limit for detection of pepsin (as determined by the manufacturer) was set at 16 ng/mL. This value was used as a cut-off to consider a saliva sample positive for pepsin. Therefore, all samples with concentrations below this threshold were considered to have zero pepsin.

Results

Patients with chronic pharyngitis and indications of chronic pharyngitis (n=32) were compared with a healthy non-GERD control group (n=31). Post-prandial saliva samples were compared for pepsin concentration. A pepsin concentration at the level >18 ng/mL displayed a visible test line on a PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) device and was marked positive. The absence of a test line was marked negative, a pepsin concentration <18 ng/mL. In the healthy individuals’ group, 10 (32%) were found to have a positive pepsin concentration and 21 (68%) were negative. In the chronic pharyngitis patient group, 25 (78%) were found to have a positive pepsin concentration and 7 (22%) were negative. Sensitivity was 78% and specificity was 68%. Positive predicted value was 71% and negative predicted value was 75%.

Reflux diagnostic questionnaires result in a positive or negative determination for the presence of reflux. A Chi-square test was used to determine if the type of RDQ, namely RFS and RSI, influenced the outcome of the diagnosis. The results show that there is a significant association between the outcome of the questionnaire, depending on which questionnaire was used to determine if the patient may have reflux disease. It was more likely a patient would be diagnosed with reflux disease if the RFS questionnaire was used compared to RSI, asymptotic significance (2-sided) P=0.000. The RFS produced significantly more positive reflux disease diagnosis results than RSI. However, when averaging the pepsin concentration across the most highly concentrated samples of all patients, a positive RFS did not correlate to a higher mean pepsin concentration from the most concentrated samples from each patient.

The mean maximum pepsin concentration from the three samples taken by chronic pharyngitis patients against the corresponding questionnaire results are shown in Table 3. The patient group with the highest concentration of pepsin was found when patients completed the RFS and scored a negative reflux disease diagnosis. The lowest concentration of pepsin from the patient group was found when the RFS scored positively for reflux disease diagnosis. Two sample t tests were performed to determine any significance between the outcome of the RFS and RSI on mean maximum pepsin concentration (Table 4). Two sample t tests show no significant difference between means of patients with a positive RFS or negative RFS and their corresponding concentration of pepsin. Two sample t tests show no significant difference between means of patients with a positive RSI or negative RSI and their corresponding concentration of pepsin. However, a significant difference occurs when the two questionnaires are used in conjunction. Two sample t tests do show a significant difference between means of patients with both a positive RFS and RSI against both a negative RFS and RSI and their corresponding concentration of pepsin P=0.452 (Table 4).

Table 4

| Statistically test applied | Difference between the mean maximum pepsin concentration and RFS | Difference between the mean maximum pepsin concentration and RSI | Difference between the mean maximum pepsin concentration and both RFS and RSI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levene’s test for equality of variances | |||

| f | 0.033 | 0.539 | 0.906 |

| Sig. | 0.858 | 0.469 | 0.354 |

|

|

|||

| |

−1.556 | 0.420 | −0.769 |

| df | 30 | 30 | 18 |

| Sig. (2 tailed) | 0.130 | 0.678 | 0.452 |

| Mean difference | −85.50235 | 26.55 | −52.63077 |

| Standard error difference | 54.94636 | 63.21 | 68.44617 |

Two sample

Chi squared (Table 5) shows no significant association on pepsin concentrations above 75 ng/mL through smoking, drinking nor having an appetite for spicy food. No significant association between pepsin concentration >75 ng/mL and patients with a positive RSI score.

Table 5

| Chi squared >75 ng/mL pepsin (n=18) | χ2 |

|---|---|

| Smoking | 0.289 |

| Drinking | 0.596 |

| Appetite for spicy food | 1.000 |

Chi squared was calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

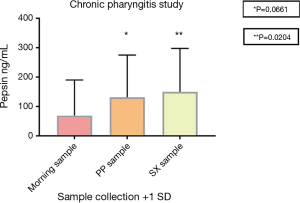

Of the 32 patients diagnosed with chronic pharyngitis 41 of 96 saliva samples had a pepsin concentration above 75 ng/mL (Table 6). This corresponded to a total of 25 patients with medium to high pepsin present in their saliva sample representing 78% pepsin positivity, only 23 samples had no pepsin present and 32 samples had low pepsin present. Six patients had all three saliva samples >75 ng/mL pepsin, four patients had two saliva samples >75 ng/mL pepsin and 15 patients had one saliva sample >75 ng/mL pepsin. Seven patients had saliva samples pepsin positive but below 75 (0 to 74) ng/mL. No patients had all three saliva samples negative for pepsin. The pepsin concentration in the saliva samples provided following symptoms were significantly different (P<0.05) to the samples provided on waking. The mean pepsin concentrations were 69 (morning sample), 131 (post-prandial sample) and 150 ng/mL (sample provided following symptoms) (Figure 2).

Table 6

| Sample collection procedure | Low pepsin concentration (ng/mL) | Medium to high pepsin concentration (ng/mL) | Mean pepsin concentration n=32 | SD | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0<16 | 16<75 | 75<125 | 125<200 | 200<500 | ≥500 | |||||

| Morning sample | 11 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 69 | 121 | ||

| PP sample | 6 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 131 | 144 | 0.0661 | |

| SX sample | 6 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 150 | 148 | 0.0204 | |

P values were calculated using unpaired

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine if patients presenting with chronic pharyngitis have a significant concentration of pepsin in their saliva samples which could be a factor causing exacerbation of their condition. Pepsin has been shown to cause tissue damage resulting in inflammation and erosion leading to pain. In the present study, a correlation has been shown between the presence of pepsin in saliva samples and patients with chronic pharyngitis. Seventy-eight percent pepsin positivity was found signifying chronic pharyngitis patients are likely to be affected by pepsin indicating reflux disease. Pepsin concentrations on waking and after symptoms were significantly different (P<0.05), indicating that the patients recognize when they have refluxed and can therefore provide a sample following symptoms. This allows a more comfortable method of diagnosis than previous diagnostic methods such as pH-metry or endoscopy, which are both invasive and time consuming. Through the use of PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) patients can be screened for the presence of pepsin non-invasively. PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) is highly sensitive and specific (12-16) for detecting pepsin and diagnosing reflux in patients.

The significance of reflux questionnaires in chronic pharyngitis patients showed significantly higher results in RSI and RFS for patients with chronic non-specific pharyngitis than in the control subjects P<0.01 (17). In the present study, when RFS and RSI were used in conjunction, there was a significant difference between the mean maximum pepsin concentration and a positive or negative result for diagnosis of reflux disease. However, if the RFS and RSI used in conjunction was the sole method of reflux diagnosis in this patient group 22% would have been diagnosed with reflux disease (Table 3). PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) was a better diagnostic marker because 78% of chronic pharyngitis patients were found to have a significant positive pepsin concentration in post-prandial samples (>75 ng/mL) indicating reflux disease. Therefore, reflux questionnaires did not give a good indication of reflux disease as many patients were diagnosed with a false negative result.

Patient demographics were shown to not have a significant impact on the results of pepsin concentrations over 75 ng/mL as shown using Chi squared test (Table 5). However, smoking did increase the number of reflux events in a previously reported study (18). Obesity, (potentially linked to weight of patients in this study) is a risk factor for GERD (19). Spicy food has also been shown to induce GERD symptoms (20). These factors may affect the likelihood of reflux disease and lifestyle factors may be adjusted accordingly. Therefore, PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) would be a suitable test for identifying reflux in high-risk groups of individuals and, chronic pharyngitis patients in this risk group should therefore be tested for reflux as they are at even greater risk.

Limitations of this study are the relatively small sample size (n=32), small sample size of patient demographic information (n=18) and the relatively small sample size of the control group (n=31).

By identifying the cause and associations with chronic pharyngitis, patients can be treated appropriately. By determining if pepsin is associated with chronic pharyngitis it reduces the over prescription of antibiotics, other treatments and invasive diagnostics.

Conclusions

PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) is a useful diagnostic tool for determining the presence of pepsin in chronic pharyngitis patients. A significant proportion (78%) of chronic pharyngitis patients had over 75 ng/mL of pepsin present in their saliva samples.

The results showed chronic pharyngitis to be strongly associated with reflux, and patients should be identified and treated for reflux. PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) may play an important role in the identification of reflux in chronic pharyngitis patients. A single high positive pepsin sample out of the three samples outlined in this study, could indicate a reflux episode and could infer reflux disease. A single high pepsin concentration will have the potential to damage the throat and if repeated over periods of time, could lead to chronic pharyngitis. PeptestTM (RD Biomed Limited) was easy to use and will provide a non-invasive, rapid method for detecting pepsin in saliva samples in a selected group of patients.

Future studies will need to investigate a larger sample size of patients and repeated saliva collection to assist in determining the correlation of reflux disease and chronic pharyngitis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoe.2018.10.01). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (Ethical Approval ID: 2017NZKY-009-02). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Issing WJ, Karkos PD. Atypical Manifestations of gastro-oesophageal Reflux. J R Soc Med 2003;96:477-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, et al. Does This Patient Have Strep Throat? JAMA 2000;284:2912-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Lai Y, Dong L, et al. Polysaccharides from Citrus grandis L. Osbeck suppress inflammation and relieve chronic pharyngitis. Microb Pathog 2017;113:365-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Jeong H, Kim KM, et al. Extra-Esophageal Pepsin from Stomach Refluxate Promotes Tonsil Hypertrophy. PLoS One 2016;11:e0152336 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray RC, Chennupati SK. Chronic streptococcal and non-streptococcal pharyngitis. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2012;12:281-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Du X, Wang F, Hu Z, et al. The diagnostic value of pepsin detection in saliva for gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a preliminary study from China. BMC Gastroenterol 2017;17:107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope 2001;111:1313-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice 2002;16:274-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:52-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harnik IG. In the Clinic. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:ITC1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw M, Dent J, Beebe T, et al. The Reflux Disease Questionnaire: a measure for assessment of treatment response in clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saritas Yuksel E, Hong SK, Strugala V, et al. Rapid salivary pepsin test: blinded assessment of test performance in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Laryngoscope 2012;122:1312-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayat JO, Yazaki E, Kang J, et al. Pepsin in Saliva and Gastroesophageal Reflux Monitoring in 100 Healthy Asymptomatic Subjects. Gastroenterology 2013;144:S118. [Crossref]

- de Bortoli N, Savarino E, Furnari M, et al. Use of a Non-Invasive Pepsin Diagnostic Test to Detect GERD: Correlation With MII-pH Evaluation in a Series of Suspected NERD Patients. A Pilot Study. Gastroenterology 2013;144:S118. [Crossref]

- Hayat JO, Yazaki E, Moore AT, et al. Objective detection of esophagopharyngeal reflux in patients with hoarseness and endoscopic signs of laryngeal inflammation. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48:318-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayat JO, Gabieta-Somnez S, Yazaki E, et al. Pepsin in saliva for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 2015;64:373-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yazici ZM, Sayin I, Kayhan FT, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux might play a role on chronic nonspecific pharyngitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010;267:571-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RR. Mechanisms of acid reflux associated with cigarette smoking. Gut 1990;31:4-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Kim A, Sanossian C, et al. Impact of obesity treatment on gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1627-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choe JW, Joo MK, Kim HJ, et al. Foods Inducing Typical Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms in Korea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;23:363-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Dettmar PW, Wang Q, Hodgson RM, Wang X, Li Y, Jiang M, Xu L, Lan Y, Woodcock AD. Chronic pharyngitis and the association with pepsin detection and reflux disease. Ann Esophagus 2018;1:17.